By Alex Kozora

Throughout the rest of the offseason, we’ll examine specific plays from the Pittsburgh Steelers 2013 season. We won’t be focusing so much on individual play, though that inevitably comes with any breakdown, but instead, we will focus on concepts used in the pro game to show not just what happened, but why it happened.

This will be an X’s and O’s series focusing on both sides of the ball. The good and bad of the Steelers of last season.

Taking a look at the Steelers’ zone blocking scheme.

Concept: Inside/Outside Zone

With the hire of Jack Bicknell Jr. in 2013, the team began to shift from its long-standing philosophy of a power running scheme – dominated by Power O – to implementing zone blocking concepts.

How does the scheme work? We’ll break it down with its basic philosophy and then show it on the tape.

In a power scheme, there is an assigned gap for the running back to run through. He isn’t asked to read the defenders in order to make his cut. If you’re running Lead Strong, the back’s assignment is following the fullback through the hole.

Not the case in zone blocking. The running back’s mission is to read the defense in order to locate the running lane instead of reading his own blockers. This is summed up by Howard Mudd in Tim Layden’s Blood, Sweat, and Chalk.

“One day I said to [running back John David Crow], ‘What do you look at when you’re hitting the hole?’ I asked him because we were always telling running backs, ‘Look at the butt of the blocker you’re following.’ So I wondered if that’s what they actually did. John said, ‘I’ll tell you what: I’m not lookin’ at [the blocker]. I’m looking at that sumbitch that’s gonna hurt me.’ Well, that really helped me because then I realized that running backs aren’t watching offensive lineman, they’re watching defenders. That’s a big difference.”

That knowledge led to the creation of the zone blocking scheme.

There are two variations of it. Inside and outside zone.

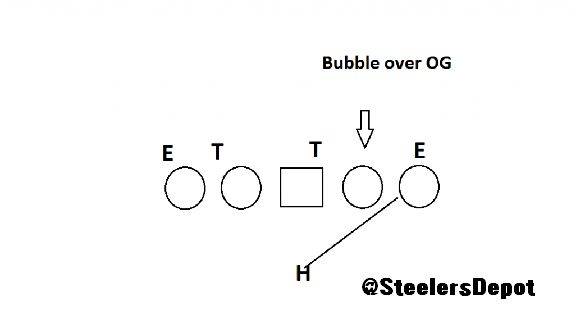

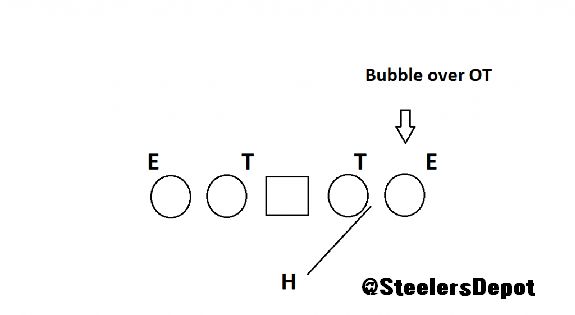

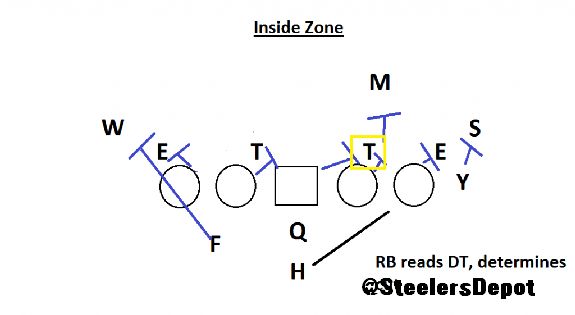

What we’re looking for on inside zone pre-snap is a “bubble.” Meaning, the playside gap that is not occupied by a lineman. This helps creates the running backs’ aiming point to run to on the handoff, although the difference is slight.

If the bubble is over the guard, the running back aims for the inside hip of the tackle. If it’s over the tackle, aim for the outside hip of the guard.

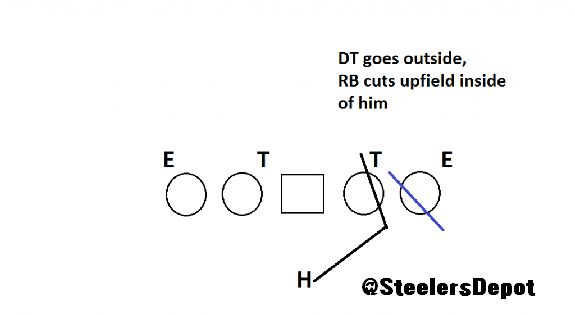

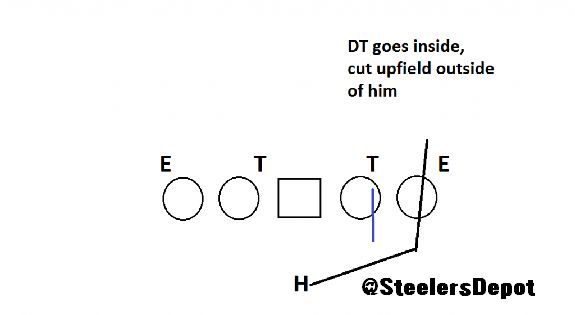

If at all possible, the back is looking to press the “B” gap. How does he determine it? Again, reading the “hat” – the helmet – of the defensive line.

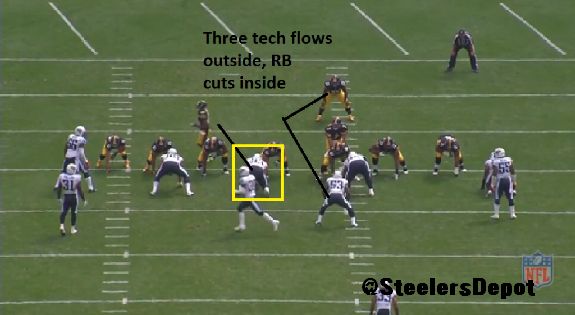

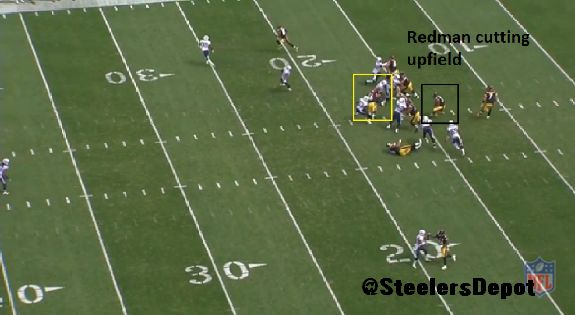

He reads the first defensive lineman to the outside of the center. If the lineman goes outside, cut upfield to the inside of him. If he goes inside, cut upfield to the outside of him.

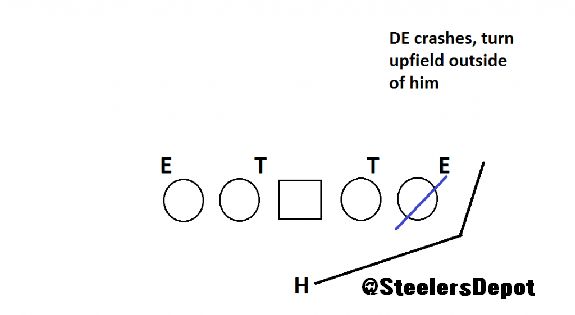

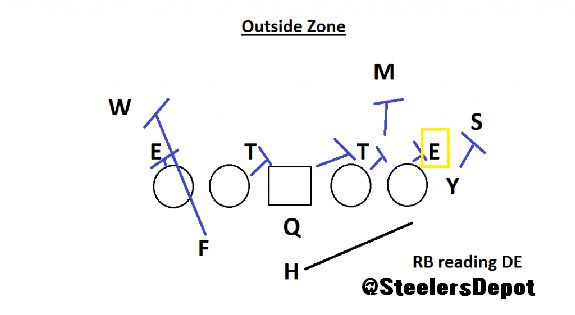

Outside zone is off tackle with the back aiming for the outside hip of the tackle or the rear of the tight end. His read? The second outside helmet of the defensive front, normally the DE in a 4-3 or the OLB in a 3-4.

If his helmet goes inside, turn upfield to the outside of him.

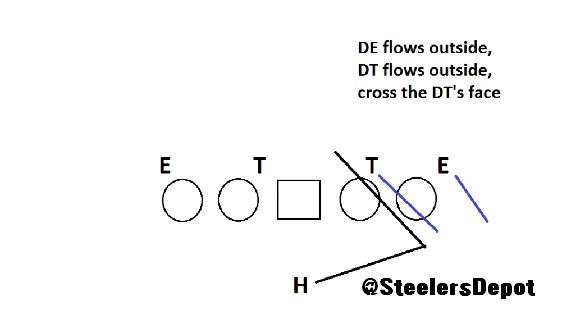

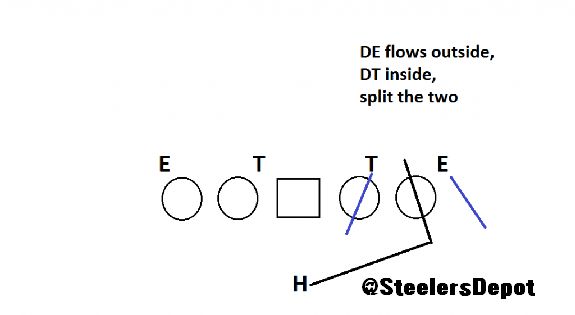

If the helmet goes outside, read the helmet of the next down lineman to the inside. The DT in a 4-3 or the DE in a 3-4. If that lineman is flowing outside as well, cut back across his face. If he’s flowing inside, split the two.

We’ve discussed it before, but we’ll delve back into zone blocking rules. Inside and outside zone are similar and one reason why coaches like to teach it – it’s fairly universal and easy to teach.

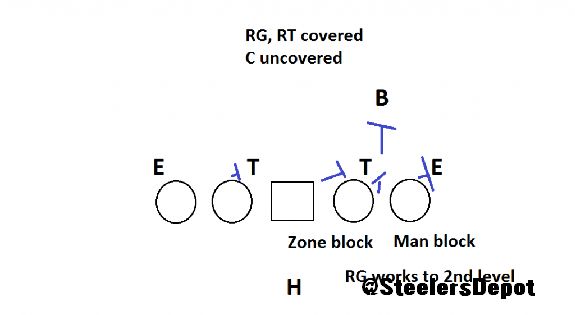

If two adjacent linemen, say the RT and RG are covered – meaning a defender lined over them – they man block.

If the frontside lineman is covered and the backside uncovered, they zone block. They double-team the defender. Often times, once the backside lineman has secured his block, the frontside lineman disengages and flows to the second level. Center and right guard zone block in the picture below.

So let’s put it all together on the chalkboard (Read: Still Microsoft Paint).

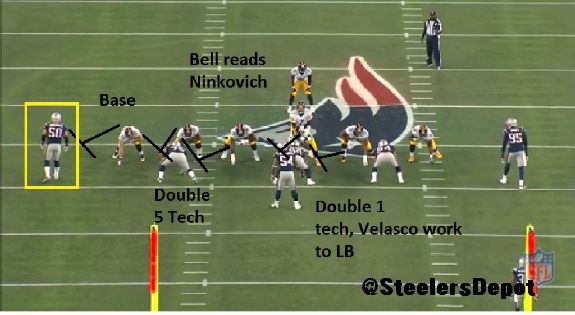

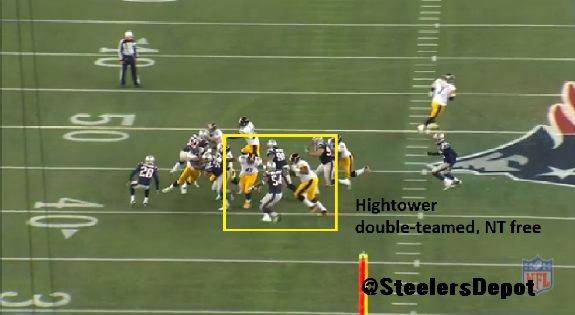

And an example from the tape. Outside zone run against the New England Patriots Week 9. Le’Veon Bell rushes for no gain. It’s an example of what happens when the blocking scheme goes awry.

Again, the blocking rules. If you’re uncovered as a lineman and your frontside teammate is covered, zone block and double-team him. That’s what Guy Whimper does with Marcus Gilbert and what Ramon Foster *should* have done with Fernando Velasco. We get base blocks from Heath Miller and Kelvin Beachum.

Bell is reading the lineman. On outside zone, read the helmet of the second outside defender. In this 3-4, it’s outside linebacker Rob Ninkovich, identified in the yellow box below. He’s inside, meaning Bell should turn upfield outside of him.

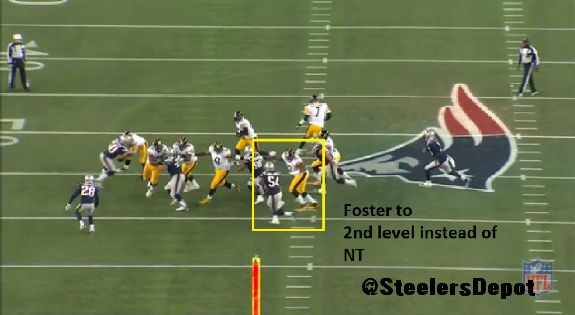

Appears to be miscommunication between the left guard and center’s assignments. Velasco is seemingly waiting to be able to pass off the nose tackle to Foster but Foster works to the second level instead. Eventually, Velasco does as well and they both end up double-teaming Dont’a Hightower.

The execution of the play is faulty. Bell seems late in his cut and the linebacker disengages Miller to make the tackle. But it shows the idea behind it.

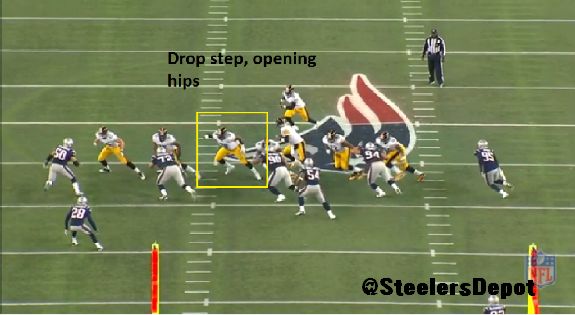

Another thing to remember. Lineman don’t fire off the ball like they do on drive, man blocks. Their first motion is a drop step that moves their shoulders and opens their hips in the direction they’re flowing.

Inside zone in Week One. Read the first lineman to the outside of the center. He flows outside so Isaac Redman cuts upfield inside of him.

Lot of information thrown out. To recap:

On inside zone, the running back is first looking for the “bubble”, the gap unoccupied by a lineman. Ideally, he’s pressing the “B “ gap. Make your cut based off of the hat of the first lineman to the outside of the center.

On outside zone, aiming point is off tackle or the rear of the tight end. Read the hat of the second defender outside of the center, possibly reading the first lineman too, to make your decision.

Blocking rules are similar between the two. If both lineman are covered, they man block. If the backside is uncovered, they zone block with the frontside flowing to the second level once the backside blocker is engaged.

As last year wore on, zone schemes were used less often and by the last quarter of the year, outside zone was practically nonexistent. But with the team’s athleticism along the line and the effective simplicity of the scheme, it has the opportunity to revive the Steelers’ run game.

Previous Film Room Sessions

Putting Pressure On Rookies

Facing The 46 Defense

Fake Wide Receiver Screen

The Steve McLendon Myth

Cover 2 Man

The Wildcat

Cover 1 And Forced Throws

Slant Flat In Red Zone

Divide Routes