Lowell Perry is an unsung Steeler. He played just six games for the Pittsburgh Steelers. He doesn’t even break into my top 1,000 all-time Steelers. However, he is a significant figure in Pittsburgh Steelers history.

MICHIGAN FOOTBALL

Lowell Perry grew up in Michigan where his father had a dental practice. He played football for the University of Michigan. A two-way player he played end on offense and safety on defense. He also handled punt returns. As a sophomore, Perry scored the go-ahead touchdown against Dartmouth near the end of the first half. On defense he intercepted three Dartmouth passes to snuff out any chance of a comeback in a 27-7 win in the second game of the season. He started six games. And led the team in receiving with 24 catches for 374 yards. He started on the Michigan Rose Bowl team that upset the undefeated California Golden Bears 14-6.

In 1951, AP named Perry a first-team All-Big Ten player. Other groups selected Perry as a second or third team all-American as an offensive end. In his senior year he continued as the Wolverine’s receiving leader for the third straight season. The Newspaper Enterprise Association named Perry a first-team all-American in 1952 as a defensive back. His 1271 receiving yards over three years set a then Michigan record that stood for 15 years. Remember, this was an era when most teams were four yards and a cloud of dust. Perry also returned 42 punts at Michigan for 351 yards, an average of 10.9 yards per return.

Lowell Perry starred on the field whether on offense, defense or as a punt returner.

DRAFTED BUT MILITARY FIRST

The Steelers assistant coach Walt Kiesling selected Perry in the eighth round of the 20-round 1953 draft. Head coach Joe Bach in the hospital so Kiesling left to run the draft. Likely both Bach and Kiesling discussed Perry as a prospect. Perry was the 90th overall pick in the same draft that the Steelers picked future Hall of Famer John Henry Johnson. Also, the same draft the Cleveland Browns selected future Steelers head coach Chuck Noll in the 20th round.

However, Perry had an ROTC service obligation and entered the Air Force following his graduation from Michigan. He played on the Bolling Air Force Base team along with Johnny Lattner. Lattner is current Steeler’s linebacker Robert Spillane’s grandfather. Both Perry and former Steeler Lattner suffered second degree burns and hospitalized when Fort Lee used lime to mark the field in October 1955.

Following completion of his military service obligation, Perry signed with the Steelers. Perry signed in January 1956 with local newspapers noting his play in Michigan and named the military service player of the year in 1955. The Pittsburgh Sun Telegraph gushed, “One swallow doth not make a spring make and neither does one player make a team. But there’s reason for optimism …. For where else could they (the Steelers) find a player who plays both offensive end and halfback and who also is one of the best safety men in the country?”

ROOKIE WITH POTENTIAL

The rookie showed his potential in his very first game in a Pittsburgh uniform. In a preseason game against the Detroit Lions, Perry scored a touchdown on a 93-yard kickoff return.

In the regular season, Lowell Perry started five of the six games he played. He caught 14 passes for 334 yards and two touchdowns. That’s 23.9 yards per reception. He tacked on two rushes for 37 yards ending up with 371 total yards from scrimmage. A 75-yard reception was the fourth longest in the NFL that season. Perry also was fifth in the league with 55.7 receiving yards per game.

As a return specialist Perry returned nine kicks for 217 yards and 11 punts for 127 yards. He averaged 11.5 yards a punt return and the 127 punt return yards landed him seventh in the league despite just playing half a season.

CATASTROPHIC INJURY

Unfortunately, Perry suffered a fractured pelvis and dislocated hip in his sixth game that ended his playing career. On November 4, 1956, future Hall of Famer Rosey Grier was among the Giants players that tackled Perry after a 23-yard run.

The hip socket “was shattered and the femur separated from the hip.” At the time of his injury, Perry a strong contender for NFL Rookie of the year. Perry remained hospitalized for thirteen weeks after the injury. He took his first steps on crutches on January 24, 1957.

As early as February 1957, a New York newspaper reported that owner Art Rooney planned to add Perry to the Steelers coaching staff. Art Rooney said, “I think losing him (Perry) as a player is the toughest thing that’s ever happened to the Steelers in 25 years.”

FROM PLAYER TO NFL COACH

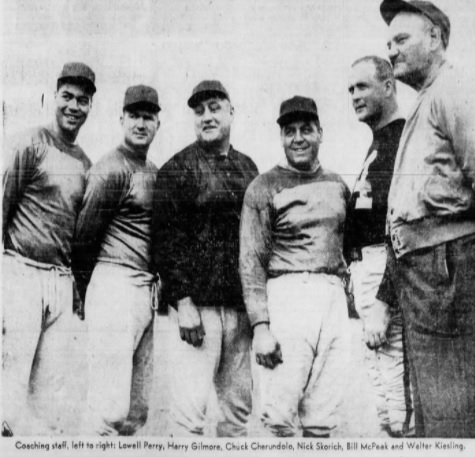

On June 1, 1957, Art Rooney signed Perry to a one-year contract as the receiver’s coach. The expectation that he recuperate in 1957 and play in 1958. In addition to Perry, coach Walt Kiesling hired Harry Gilmer as the backfield coach. They joined holdovers Nick Skorich, Bill McPeak, and Chuck Cherundolo all former Steelers players.

Buddy Parker took over head coach from Walt Kiesling, who was in ill health, on August 28, 1957. Already in training camp with two preseason games played, Parker committed to keeping Kiesling as an assistant and the entire staff including Perry for the 1957 season. The Steelers improved from 5-7 in 1956 to 6-6 in 1957.

Buddy Parker reorganized the team making coaches full-time. He also designated Lowell Perry to return as a player in 1958 after one year of coaching the receivers. Perry indicated he would play when his leg healed completely. However, in July Perry notified Art Rooney that he decided to pursue a law degree in Michigan. During his time with the Steelers Perry began studying law at Duquesne University. The Steelers retained Perry as a scout in the Midwest so that he could continue his studies and contribute to the team in 1958. He remained on the payroll as late as December 1959.

SIGNIFICANCE OF PERRY COACHING

The significance of Lowell Perry’s coaching is that he became the first African-American coach since Fritz Pollard who was the co-head coach of the Akron Pros in 1921 and head coach of the Hammond Pros for one game in 1925. Thus, Lowell Perry became the first African American assistant coach in the NFL. At least in the modern era. This happened seven years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

New York Giants claimed Emlen Tunnell was the first black NFL assistant coach in May 1963. But the Pittsburgh Press pointed out that Perry preceded Tunnel by six years.

Perry appreciated that Steelers owner Art Rooney helped him achieve his law degree by keeping him on the staff as a scout even after he moved back to Michigan to complete his degree in Detroit.

Perry on Art Rooney: “I certainly hope, for Mr. Rooney’s sake, that the Steelers win this year, because, in my estimation, Art Rooney is the finest gentleman in the world of sports, today.” As published in the Pittsburgh Courier July 29, 1961.

HIS LIFE’S WORK

After leaving the Steelers, Lowell Perry got his law degree at Detroit College of Law in 1960. Then he received a federal law court clerkship in Detroit that June. He joined Chrysler where he rose to be a plant manager. The first African-American to do so in the U.S. auto industry.

In 1966, Lowell Perry was the Steelers color analyst with play-by-play announcer Joe Tucker for games broadcast on CBS. Another first. Perry the first African-American broadcast NFL games on national television. He resigned after a year due to his job obligations.

Also, Lowell Perry was a charter member and served on the board of directors of NFL Charities. He administered grants awarded by NFL charities in 1973 and served there for many years. Today, the same organization is the NFL Foundation that continues issuing grants, charitable work, and youth initiatives.

In 1975, President Gerald Ford appointed Perry Commissioner of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Art Rooney attended Perry’s swearing in ceremony in the Rose Garden of the White House. As EEOC Commissioner, Perry spoke to the National Urban League saying that companies insisted on “superman performances from minorities while accepting mediocrity from others.” This became a theme of many of his speeches. Adding “But we shouldn’t fight destiny. We should continue to be Supermen.”

He returned to Chrysler afterwards. Perry returned to government service in 1990 as Michigan’s Department of Labor Director. He retired in 1999.

LEGACY

For their part, the Steelers did not hire another African-American coach until 1970. Chuck Noll hired Lionel Taylor as a receiver coach, his first NFL coaching job. Noll denied factoring race into the decision to hire Taylor. Saying, “He was signed completely on what we think is his ability to do a job for our coaching staff.” Taylor coached in Pittsburgh until 1976 winning two Super Bowl rings. Then he went on to coach 22 more years at various levels and teams.

Perry’s eldest son Lowell Jr. graduated from Yale University. He became the marketing director for the Seattle Seahawks where he and Chuck Knox set up a drug outreach program for students. He worked for the Sisters of Charity Foundation of Cleveland. Currently, he is Executive Director of YUMA Crossing National Heritage Area Corporation which is working on water conservation on the Colorado River.

His son Scott played basketball at Oregon then Wayne State. As an assistant coach at Michigan, Scott instrumental in their NIT win in 1995. Named head coach of Eastern Kentucky University in 1997. He coached there until 2000 when the Detroit Pistons hired him as a front office executive. Currently, he is general manager of the New York Knicks.

I could not find much information about his daughter, Merrideth Perry Moore. I did find one article that mentioned her work in online education. But she did make a statement at her father’s funeral that epitomized him.

Lowell Perry died of cancer in January 2001 at the age of 69. His daughter Merrideth remarked, “My father used to say that you make a living by what you earn, but you make a life by what you give.” Lowell Perry was an underreported trailblazer and a significant part of Pittsburgh Steelers history. An unsung Steeler.

YOUR MUSIC SELECTION

I always like to include some music. Weaker men may have succumbed to their injuries and disadvantages in life. But Lowell Perry was a strong man, a superman, that overcame adversity to be remarkably successful. And he gave what he received to others. Here is Only the Strong Survive by Jerry Butler the Iceman.