For those of you who listen to The Terrible Podcast (and if you’re not, you should check it out!), you heard David Todd and Dave Bryan pose the question a few days ago of whether Pittsburgh Steelers wide receiver Eli Rogers will start the season on RESERVE PUP or be activated to the 53 roster. The slot WR suffered an ACL injury in the Divisional Round playoff game last January and underwent surgical repair shortly afterward. He was scheduled to be a restricted free agent the past offseason but in light of the injury, the Steelers chose not to tender him, waiting to see his health status this summer.

Rogers underwent ACL repair as well as repair of a torn meniscus which also occurred at the time of his injury. Fortunately, there was no report of an associated MCL tear, which is not uncommon. As a free agent, he spent his offseason rehabbing his knee and has had a fairly quick recovery, visiting with teams and undergoing physical evaluations by team physicians a mere 6 months later. Rogers returned to his home with the Steelers with a one-year contract and was placed on the Active PUP list as training camp began.

Rogers was seen running sprints at Latrobe this week and he looked good. Although fellow wide receiver Marcus Tucker (hoping to make the transition from practice squad to active roster) sustained an ankle injury catching a TD at practice on Thursday which held him out of the annual Friday Night Lights practice, the injury appears to be minor. As the Steelers head towards their first preseason game with all of the wideouts on the 90 man roster essentially healthy, is there room for Rogers?

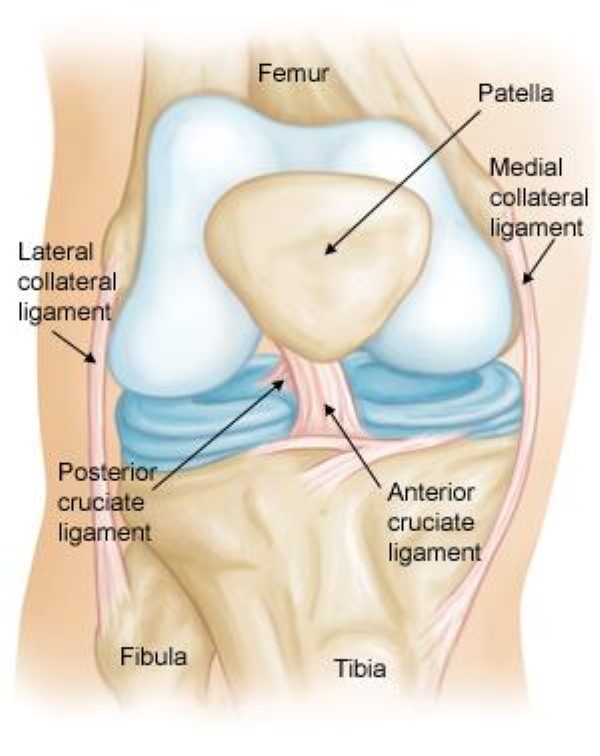

First, a quick refresher course on ACL injuries, starting with the anatomy of the knee ligaments:

1The anterior cruciate ligament runs diagonally in the middle of the knee. It prevents the tibia from sliding out in front of the femur, as well as provides rotational stability to the knee.

2orthoinfo.aaos.org

Also courtesy of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons:

- Grade 1 Sprains.The ligament is mildly damaged in a Grade 1 Sprain. It has been slightly stretched, but is still able to help keep the knee joint stable.

- Grade 2 Sprains.A Grade 2 Sprain stretches the ligament to the point where it becomes loose. This is often referred to as a partial tear of the ligament.

- Grade 3 Sprains.This type of sprain is most commonly referred to as a complete tear of the ligament. The ligament has been split into two pieces, and the knee joint is unstable.

- Partial tears of the anterior cruciate ligament are rare; most ACL injuries are complete or near complete tears.

- About half of all injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament occur along with damage to other structures in the knee, such as articular cartilage, meniscus, or other ligaments.

As mentioned, Rogers sustained an ACL tear as well as a meniscal tear, so there was never a question as to whether Eli would have surgery. As I have explained in the past, non-operative management for ACL tears doesn’t work out well (yeah, I was talking about Dolphins QB Ryan Tannehill).

To surgically repair the ACL and restore knee stability, the ligament cannot just be sewn back together – it has to be reconstructed. This is done with a graft which serves as a scaffold for the new ligament to heal onto. Different types of grafts are used, ranging from cadaver grafts to tissue from somewhere else in the leg: the patellar tendon, the hamstring tendon or the quadriceps tendon. In a 2012 survey of NFL and NCAA Division 1 team orthopaedic surgeons, 86% of them reported that they use patellar tendon reconstruction. Here is a brief video of a schematic of a basic ACL repair. For those interested, here is a video of an actual ACL repair from Dr. David Geier, a sports medicine specialist who is also a good follow on twitter (@DrDavidGeier).

OK, so Rogers had his knee fixed. He says he’s feeling great and will be ready to go. Then again, all professional athletes say that, and many of them probably believe it. I’ll never be the one to argue with an NFL athlete’s insane work ethic or positive outlook. Then again, data is often helpful. Let’s look at some data for ACL recovery times for NFL players to answer that question.

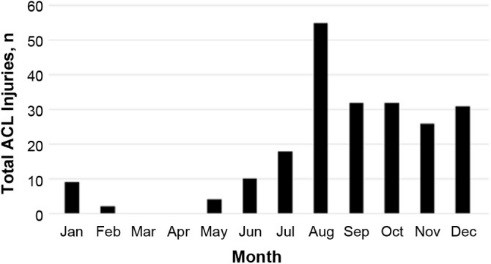

This isn’t as easy an answer as you might think because a lot of ACL injuries occur early in the season. Players who wind up on IR don’t come back until the following season, so it can look like a 12 month recovery for many of them. A study in the Orthopedic Journal of Sports Medicine reviewed all ACL injuries in NFL players from 2010 to 2013. They found that a majority of ACL injuries occur in preseason:

This makes sense because there are many more players on the field (90 as compared to the regular season roster of 53). Based on this, most studies look at return to play as an NFL athlete playing the following season.

Everyone always talks about how miraculous Adrian Peterson’s recovery from his ACL injury was. He suffered the knee injury on Christmas Eve in the 2011 Week 16 win over the Redskins. He underwent repair of his ACL and MCL 6 days later. After obsessively working on his rehab in the offseason, he was ready to go Week 1 the following season. Peterson ended the 2012 season a mere 8 yards shy of the all-time rushing record set by Eric Dickerson. Certainly a pretty good recovery by the Vikings RB, but it was more his performance that was remarkable, not the time it took to return to play.

The Richmond Joint and Bone Clinic looked at ACL recovery in their own series of NFL players in 2010. They found that 63% (31 of 49) NFL players returned to play at an average of 10.8 months – not much different from what Peterson accomplished. There was no difference between athletes who returned to play and those who never set foot on the field in a regular season game with regard to player age, position, and the type and number of procedures performed. Not surprisingly, places drafted in higher rounds (average of round 3.4) were more likely to play again after recovery. Most likely, those drafted in later rounds (average round 6.4) never got another chance on a roster. A Round 4 draft rank seemed to be the dividing point.

The NFL Orthopaedic Surgery Outcomes Database reviewed 559 NFL athletes with ACL injuries. They found that players required an average of 378 days (1.07 years) to recover from ACL repair and their careers wound up shorter on average. 80% of players returned to play and most players get to 80% of their pre-injury performance level. Unlike other skill players, QBs experienced no decrease in career length.

Where Peterson was superhuman was the quality of his play after his return. Most athletes have a drop-off in performance in the first season (and sometimes the second) back. In a 2017 review of player outcomes in The American Journal of Sports Medicine, NFL players were found to have a decrease in performance in seasons 1, 2, and 3 following recovery.

Players also earn less after an ACL injury and repair. A group at the Medical School of the Thomas Jefferson University looked at the financial impact of ACL injuries and career length for NFL players. They found that higher paid players (>$2M per year) had the same career length as their cohorts that didn’t have that injury. For players earning less, fewer players remained on a roster at 1, 2 and 3 years after injury. This correlates with the data based on draft pick round.

So what about other WR recoveries? 49ers Jerry Rice still holds the record. In 1997, he blew out his ACL in Week 1 and returned for the Week 15 game. By his own admission, he came back too fast. The reality is that players often feel ready to play long before the ACL graft has totally healed. While most doctors will allow their patients back on the field to practice at 6 months, studies show that it takes 18 months for the healed ACL to have full strength. That may not matter too much though. As reported in the Journal of Orthopedic & Sports Physical Therapy, unilateral deficits in the reconstructed ACL leg may not be evident when performance (they used modified NFL Combine assessment tests) is evaluated…meaning that the leg with the repaired ACL may not perform as well but that may not affect overall test results.

It’s great to see Eli Rogers running sprints. As far as I know, he hasn’t done any cutting in his workouts, which is a crucial move for a wide receiver. I fully expect Rogers to play in the 2018 season but it’s hard to imagine that he will be ready to join his teammates for full practice in the next month, so far ahead of what the typical NFL player is able to do and even faster than Adrian Peterson, who really isn’t human. With that in mind, it doesn’t make sense to spend a roster spot on him at this point. Barring injury to other wideouts that leaves the Steelers thin at the position, expect Rogers to start the season on the Reserve PUP list. But you can also count on him finding his way back to getting a helmet on gameday this year.