The Pittsburgh Steelers report to training camp in less than three weeks. The players should be happy that it is 2024, not 1947. And that their coach is Mike Tomlin, not John “Jock” Sutherland.

That is not a commentary on Tomlin. The Steelers have one of the NFL’s most physical camps. Tomlin, who loves wearing black, long-sleeved shirts in extreme heat, would have his players at Saint Vincent College for six weeks if he could. Maybe more.

Unfortunately for him — and other coaches of like mind – the concessions NFL owners make while generally owning the NFLPA in CBA negotiations come at the expense of coaches like Tomlin. Less practice time in pads. Limits on how rigorous of a training camp they can run.

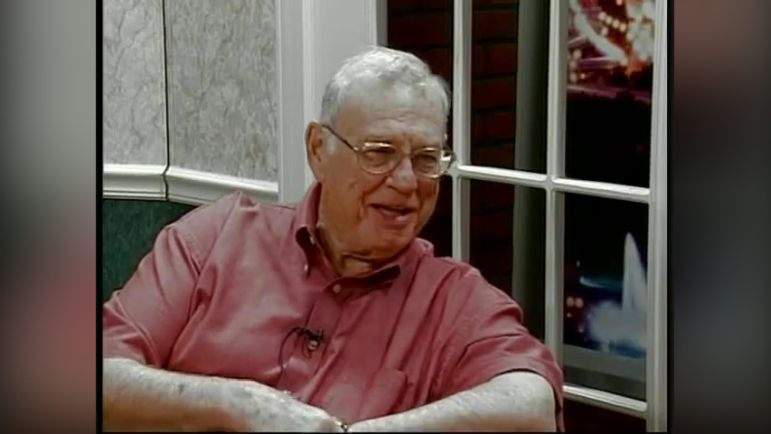

Sutherland faced no such restrictions in the two years he coached the Steelers before dying in 1948 at the age of 59, shortly after doctors discovered that he had a brain tumor.

Sutherland was a Pittsburgh legend long before he became the Steelers’ head coach. A two-time All-American at Pitt, he later succeeded his mentor, the legendary Glenn “Pop” Warner, as the Panthers’ head coach. He figured prominently in the string of national championships Pitt won during that era as a player or coach.

Sutherland led the Steelers to their only playoff appearance prior to the merger. While researching an article on WR/DE Val Jansante, one of the star players on that team, I came across a couple of training camp stories that were nothing if not a sign of the times.

I found them in Steelers vice president Art Rooney Jr.’s book, “Ruanaidh,” a fun read that offers a comprehensive history of the Steelers and Rooney family.

Rooney is one of the architects of the Steelers’ 1970s dynasty, the player personnel chief who helped Pittsburgh ace NFL drafts and transform the once-woebegone franchise. In 1947, he was a ballboy while the Steelers spent training camp at Alliance College in the northwest corner of Pennsylvania.

As Rooney wrote in “Ruanaidh,” Sutherland ran such an exacting camp that players regularly slipped out of the Alliance dormitories at night, never to return. So many left that Sutherland posted assistant coaches outside of the dormitories to stem the exodus.

“They appealed to the players’ pride but continued to torture them on the practice field,” Rooney wrote. “Most of these players were World War II veterans and not quitters. I heard a guy who had been in combat say that he ran harder for Jock than he did when the Germans were chasing him.”

Nothing better illustrated how grueling camp was than something that put Rooney in an unenviable position. Sutherland had team trainer Doc Sweeney put what Rooney wrote were “Mother’s Oats” in the water buckets. Players were so desperate to cool off after one practice that a couple of them started pouring what, Rooney recalled, looked like vomit on themselves. Rooney was ordered to put a stop to it.

“So I tipped the buckets over,” Rooney wrote, “and the unappetizing mess spilled out on the ground. Val Jansante was standing there with a thick oatmeal paste in his hair and all over his face. He gave me a look I still remember and said with pure venom, ‘Kid, you’re a mean little prick.’”

A different time indeed.