Val Jansante is a long way from his father earning acclaim as a receiver in the latter half of the 1940s — when some coaches considered the forward pass only slightly less subversive than socialism.

His distance from the elder Val Jansante starring for the Pittsburgh Steelers is literal too.

The younger Val Jansante – he and his father have different middle names – lives on the plains of western Nebraska. A community liaison for U.S. Representative Adrian Smith, his past and present intersected in Washington, D.C., a couple of years ago.

While Jansante was touring the Smithsonian Institute, he met a woman who held a lofty position at the iconic museum. Jansante told her that his father had played for the Steelers and that he still had one of his jerseys. She asked if he would like it displayed in the Smithsonian.

Jansante had to politely decline because the jersey was not 100 percent authentic. The elder Jansante had taken the No. 54 off his jersey – they were sewn on back then – and his son later replaced it with the decals that are used today.

No one knows why Val Jansante removed the numbers, but it serves as a metaphor every bit as powerful as the hands that earned him the nickname “Glue Fingers.” Jansante, who died in 2008 at the age of 88, never wanted to draw attention to himself.

Indeed, if he were alive today, he would be much more inclined to tell stories about Easter egg competitions with his children than he would of his exploits at old Forbes Field.

“He was just a down-to-earth guy,” Val Jansante said. “You would have no clue that he had any kind of fame at all.”

That is hardly hyperbole.

“One of my sisters and one of my brothers were in high school before they ever found out that Dad had played for the Steelers,” said Chris Jansante, the oldest of the nine living Jansante siblings. “He never used any superlatives about his own playing. He was extremely humble. When people found out he was a Steeler, he downplayed it. Not that he wasn’t proud of it, but he wasn’t promoting it in any way.”

Had Jansante been so inclined, he could have said plenty about a Steelers career that spanned from 1946-51:

- Jansante led the Steelers in receiving in five consecutive seasons, a team record that stood until the mid-2000s when Hines Ward broke it.

- He caught 10 passes in a game – twice — despite playing most of his career in a single-wing offense.

- He drew comparisons to Green Bay Packers legendary pass-catcher Don Hutson while also excelling on defense as a two-way player.

- Jansante recorded 8.5 sacks in 1950 as a defensive end, which would have led the NFL had sacks been an official statistic.

“There wasn’t any better than Jansante,” Art Rooney once said, according to “The Chief,” Jim O’Brien’s book on the Steelers founder.

The Chief’s son and namesake can vouch for that.

Long before helping the Steelers ace NFL drafts (hello, 1974), Art Rooney Jr. served as a team ballboy. One of the architects of the franchise’s 1970s dynasty still remembers how Jansante could flat-out play.

“He could run and knew how to shake and could catch anything,” Rooney told Steelers Depot. “Boy, in today’s game, he’d be a superstar. He was a real good athlete and a real good guy.”

His children, among countless others, knew the latter. For years, they saw examples of the former.

Tim Jansante, who first learned his father had suited up for the Steelers when he was a freshman in high school, played football for him as a sophomore at Bentworth. The year was 1967, and Val Jansante was 47 — almost 20 years removed from playing in his last NFL game.

After practice one day, he gathered the players and told them they were all going to run the 40-yard dash. Since they were wearing pads, Jansante told the player that he would run backward.

“He smoked the whole team,” Tim said, laughing.

As athletic as Val Jansante was – at 6-1, he only needed to take half a step before dunking a basketball in his prime – he was just as competitive. When he broke his wrist at the age of 70, it happened while he was playing pickup basketball.

And that barely slowed him down.

“He was just a freak of nature,” said Zeb Jansante, another of his sons. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

It was Zeb who connected his father’s wondrous athleticism to bygone Steelers days.

While playing football at California (Pa.) University, Zeb read an article about his father titled “The Forgotten Receiver.” After graduating from Cal, he went to graduate school at Pitt and stopped at Hillman Library one day. He started combing through microfilms of Pittsburgh newspapers.

The next time he was home, he dropped a thick pile of papers he had printed on the kitchen table where his father was sitting. How come he had never told his kids how good of a player he had been with the Steelers?

Zeb did not get much more than a shrug, which compelled him to keep digging. He spent years reconstructing his father’s Black and Gold career from black and white print, coming across one wow moment after another.

Fittingly, it was Zeb who started nominating his father for various Halls of Fame, and Jansante is a member of a handful of them. They include the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame, the Pennsylvania Hall of Fame, and the Duquesne University Hall of Fame. He was inducted into the Mid-Mon Valley All Sports Hall of Fame in 2000 — the same year as Joe Montana.

Bill Priatko emceed the Mid-Mon Valley induction ceremony, and he still remembers how humbled Jansante was by the honor. As the oldest-living Steelers player, Priatko can recall a lot more about Jansante, whom he had watched at Forbes Field. That includes a conversation he once had with Jack Butler, one of the greatest defensive backs in Steelers history and a Pro Football Hall of Famer.

“Jack said to me years back, ‘Val Jansante was an outstanding offensive and defensive football player.’ Jack knew this firsthand because he had a tough time covering Val in practice,” Priatko said.

Jansante’s most memorable season came in 1947. It was an unlikely Steelers campaign fleshed out by an unlikely source.

Steve Massey grew up in Mississippi, coming of age when the Steelers won Super Bowls with regularity and extended their popularity far beyond Pittsburgh’s belching steel mills. A history major at Southern Mississippi, he tapped into his love of research after becoming enamored with the only Steelers team to make the playoffs prior to the 1972 “Immaculate Reception” season.

He wrote “Starless: The 1947 Pittsburgh Steelers,” and it was published in 2018. It chronicles the season in which the team went 8-4 in the regular season and came within a game of playing for the NFL Championship.

The title of the book notwithstanding, Jansante excelled in 1947, catching 35 passes for 599 yards and five touchdowns. His 17.1 yards per catch is a ridiculous number for that era—and only a yard less than what George Pickens averaged in 2023, which led the NFL.

“They didn’t throw the ball very much, and they didn’t have [Terry] Bradshaw or [Ben] Roethlisberger back there throwing either,” Massey said of the Steelers teams for which Jansante played. “In the single wing, the quarterback is the guy that gets the ball the least amount. It’s the tailback that gets it, so Johnny Clement was the guy that was throwing to him.”

Clement threw for 1,004 of their 1,410 passing yards in 1947, Jansante accounting for 42.5 percent of the team’s receiving yards. The Steelers lost 21-0 to the Philadelphia Eagles in the East Division playoffs and the next year stumbled to 4-8. Despite the down year, which came after coach Jock Sutherland’s untimely passing (Jansante served as a pallbearer at his funeral), Jansante caught 39 passes for 623 yards and three touchdowns.

Two seasons later, he unofficially led the NFL in sacks.

Jansante qualifies as one of those Steelers who might not get their due for several reasons.

He played in the leather-helmet era when the NFL only had pockets of regional popularity. He also spent most of his career with a Steelers organization — Jansante had an abbreviated stint in Green Bay following a trade to the Packers — that did not start winning until long after he had played his last down.

“I think he needs to be in the Steelers Hall of Honor,” Massey said. “They need to keep that team history alive.”

The funny thing is that Jansante would have been the last person stumping for such an honor, something that can be traced to a tiny borough that is tucked into the corner of southwestern Pennsylvania.

Val Jansante left Bentleyville for Duquesne, the U.S. Navy (he served during World War II, after the Steelers drafted him in the 10th round in 1944), and the NFL, but Bentleyville never left him.

Small-town sensibilities shaped him; he never saw himself as bigger than from where he came. Even if he had, he would not have had time to regale people with tales of his Steelers playing days.

Jansante had a wife with and a house full of kids to feed after retiring in 1951.

He had made no more than $5,500 a season in the NFL, and that was after Art Rooney gave him a $500 raise following his rookie season. While that was a comfortable salary back then, it by no means made him wealthy.

Nor did his second career.

Jansante taught drivers education and coached football, girls’ basketball and golf (among other sports) for years. He supplemented that living with side jobs that included working as a lifeguard and a security guard and giving private driving lessons.

His family, big as it was, grew exponentially because of how many other kids he impacted. Jansante coached football at three different high schools, including Bentleyville/Bentworth (he had a second stint at the school after it became Bentworth), and he did not just drill into his players the importance of mastering the game’s fundamentals. He also talked to them about life after football and making sure they had a plan for it.

His life went beyond just providing for his wife and kids.

“Every single time I would ask Dad if we would go down to the park and throw a ball with me or take me to the court to play basketball, he never once said no,” recalled Jill Wales, a 1,000-point scorer in high school despite playing just two seasons. “He always made time and went with me.”

Ultimately, the biggest reason Jansante why never indulged in posterity may be the simplest one: he just was not wired that way. He was the type who instead of walking up a flight of stairs would sprint up them. Always on the move, his DNA did not allow him to sit around and talk about the glory days.

“When he passed away at 88, he looked like he could still go on a court and play basketball,” Tim Jansante said.

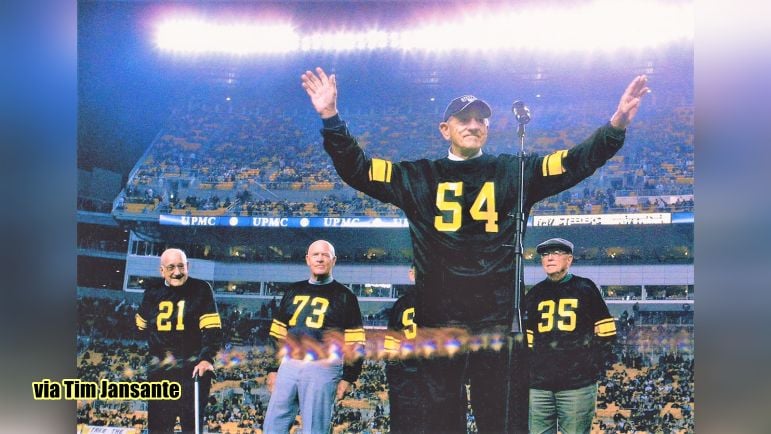

A year earlier, Val Jansante had been among those from the 1947 team recognized before a 2007 game at Heinz Field. An honorary team captain, Jansante soaked in the applause, showing a side his children rarely saw since Jansante had been a legend in many minds except for his own.

“My dad was just a very humble, phenomenal person,” Zeb Jansante said.

Zeb followed his father into education. He had been the longest-serving high school principal in the state of Pennsylvania when in 2020 he became an assistant superintendent in the Bethel Park School District in suburban Pittsburgh. Four his siblings taught or coached — or both – similarly inspired by their father. Tim Jansante is the mayor of his dad’s beloved Bentleyville.

Val Jansante impacted his children in all manner of ways. His son, Val, recalls shining his football cleats and re-lacing them after every Thursday practice when he played for his father. He wanted them to look brand new on Friday nights since his dad wore a coat and tie for games.

One of Chris’ fondest recollections is from Easters when he was a pint-sized kid and the Jansantes would hard boil and dye eggs. The kids would take turns standing across from their father, each with an egg in their cupped hand.

The goal was to see if any of them could crack the shell on their father’s egg before he cracked the shell on theirs when they joined hands. Val, having fun with his kids, would slip his thumbnail in front of his egg to protect it. For years, they wondered why his egg never seemed to crack on impact while theirs did.

“When we all figured it out, we had a great big laugh,” said Chris, who is now 75 and lives in the Pittsburgh area. “He was a package you couldn’t believe: a devoted family man who cared deeply about his wife, children and church. So humble, yet so extraordinarily athletic, quick-thinking, innovative and constantly humorous. He was truly a joy to be around.”