In the early goings of this season, the Pittsburgh Steelers’ offense has looked less like a well-oiled machine and more like a project in need of serious tinkering. From Offensive Coordinator Matt Canada’s questionable play-calling to rookie QB Kenny Pickett’s inconsistent decision-making and accuracy, not to mention an offensive line that has struggled to hold its ground—there’s plenty of room for critique.

Yet, in this sea of offensive woes, there’s a beacon of hope: the underutilized play-action pass. This particular strategy has been notably absent from Pittsburgh’s playbook, largely due to franchise legend Ben Roethlisberger’s preference for traditional dropback passing. Remarkably, the trend has persisted even with the transition to a new OC in Matt Canada and a new QB in Kenny Pickett.

According to ESPN statistics, the Steelers have ranked near the bottom in play-action usage for the past two seasons, utilizing it at a meager rate of 18%. But as we’ll explore, perhaps it’s time for this gold coin in a junkyard offense to take center stage.

It’s no accident that when you examine the NFL’s play-action usage, you’ll find some of the league’s most dynamic offenses leading the pack—think Miami Dolphins, Los Angeles Chargers, Minnesota Vikings, Detroit Lions, and Buffalo Bills. The correlation is unmistakable. Even for teams whose running game may be less than stellar, employing play-action serves a crucial function. It manipulates the positioning of linebackers and safeties, creating those essential throwing lanes that can into a game-changing play.

Pittsburgh saw it with their own eyes on Monday Night vs. the Cleveland Browns.

Zeroing in on George Pickens’ electrifying 70-yard touchdown, it’s fascinating to see how the play-action, coupled with the pulling center, profoundly impacts the WILL linebacker. The linebacker (No. 6) expands laterally, parting the sea for Kenny Pickett, who capitalizes with a perfectly executed throw downfield.

Browns LB Jeremiah Owusu-Koramoah (No. 6) knows they got him.

Now, it wasn’t all sunshine and rainbows for the Steelers when they went play-action.

Take, for example, the play that resulted in Gunner Olszewski fumble. The hiccup here wasn’t necessarily in the play call, but rather in its execution.

Here, we see another shotgun-based play-action, featuring a quarter-roll from the quarterback. The route concept essentially evolves into a more intricate version of the flood concept: WR Calvin Austin runs a clear-out vertical, George Pickens breaks out in a burst release speed out, and running back Najee Harris has a check-release flat.

The look isn’t entirely clean for Pickett as the presence of the hook-curl defender definitely spooks him. However, if he throws this behind Pickens this is an easier pitch and catch. Instead, he checks it down to Olszewski and chaos would ensue (purposely cut it for you so you didn’t have to endure it again, you’re welcome).

What we ultimately seek from any young quarterback is the ability to learn and grow from their errors. I’m fairly certain Pickett was scrutinizing this very play post-drive, huddled with QB Coach Mike Sullivan, scrolling through images on the Surface Tablet, and identifying how he could’ve connected with Pickens.

And indeed, it seems those sideline lessons paid off. Later in the game, the Steelers returned to the same concept—and this time, executed flawlessly.

Operating out of a heavier 21 personnel, twins right bunch formation, they had Pickens lined up in the slot running the same burst-release speed out and Austin running clear-out skinny post.

Pickett again goes through the play-action quarter-roll with the hook-curl defender retreating. However, the lessons learned seem to crystallize in this moment. Pickett nails the throw with exceptional ball placement, delivering what could easily be considered one of the night’s best passes to George Pickens. He places the ball inside, skillfully keeping it away from the lurking defender—a textbook example of a great rep.

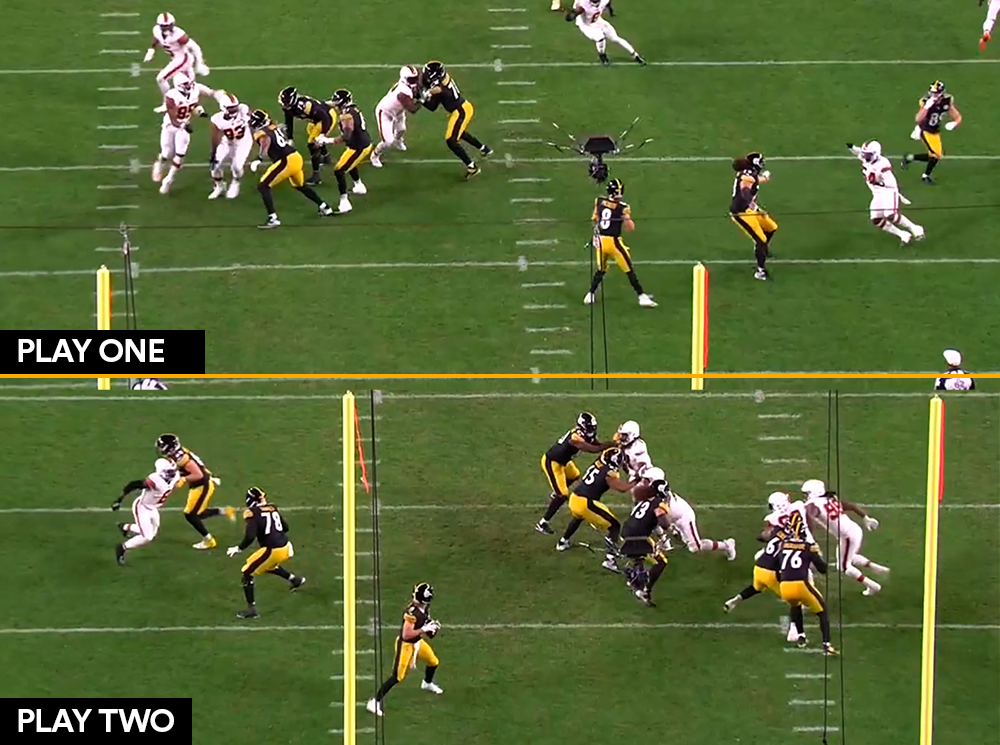

While these play-action plays represent just a sliver of the Steelers’ offensive playbook, they’re precisely the sort of plays that could jump-start the offense and help Pickett find his groove. One challenge, of course, is providing Pickett enough protection in the pocket. But if you look below at the pocket formation in those two play-action quarter-rolls, it’s evident that this strategy could be the start of a solution.

It doesn’t get much cleaner than that.

Beyond just the immediate benefits, it’s worth noting that these play-action quarter-roll concepts aren’t new to Pickett. They were a staple during his tenure at Pitt under Offensive Coordinator Mark Whipple. Integrating plays that your young quarterback is comfortable with—plays that contributed to him becoming a first-round talent—can often be a recipe for success.

When you look at Pickett’s college stats, it’s clear that play-action was a strong suit for him, especially in his senior year. Pitt used play-action about on 26% of Pickett’s pass attempts, and he responded by throwing 18 touchdowns to just four interceptions.

We’re getting to the point where referencing Pickett’s time at Pitt may start to feel repetitive. But the fact remains: unlike Ben Roethlisberger, Pickett has shown that he can excel with play-action. It’s an aspect of the game that should be more prominently featured in the Steelers’ offense.

While the Steelers offense has struggled in various facets, play-action appears to be a bright spot worth exploiting. As Pittsburgh looks to enhance its offensive capabilities, integrating more play-action could offer not just an effective tool, but also a comfort zone for their young quarterback. It’s a win-win that’s hard to ignore.