I just so happened to have left the television on while writing my articles late one night early this week when something on the news happened to catch my eye—or my ear, rather. It was a short news piece about a new approach to protecting the brain against traumatic brain injury due to sloshing, and I find it utterly fascinating, and potentially revolutionary. I hope that you do as well.

The concept is actually a rather simple one: a collar that one wears around the neck, which compresses the jugular, reducing blood flow from the brain, and thus adding more volume inside the cranium—and less space in which the brain can slosh around.

The idea was inspired by the common woodpecker, a bird that beats its head, according to the report, in excess of 80 million times over its lifespan without suffering the repercussions of brain trauma. The woodpecker’s tongue system is a bit more complicated than ours, wrapping itself around the bird’s skull, which produces the same effect that the collar proposes to replicate.

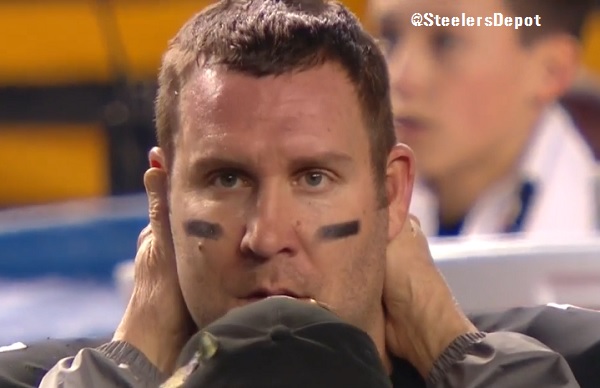

That collar is the invention of Dr. Julian Bailes, among the leading researchers in the field of neurological trauma research. He was featured in the recent Concussion movie—and was the Pittsburgh Steelers’ team doctor for a decade, as well as Mike Webster’s personal doctor after he retired.

Webster was a Hall of Fame Steelers center whose post-career struggle with dementia and the eventual discovery of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in his brain after his death was the catalyst for our growing understanding of the nature of head injuries in relation to the sports world, and in general.

Bailes’ device was originally an idea first catalyzed by Dr. David Smith after somebody quipped during a 2007 conference that the problem would be solved “if somebody can figure out how a woodpecker can smash its head into a tree and fly away without a headache”. Smith contacted Bailes about his idea in 2009.

Back to the collar, however, it is a proposal that I find fascinating for two reasons, but I will give the concrete one first, and that is the positive results that have already been achieved from an independent clinical trial carried out by Dr. Gregory Myer.

The findings of his study, at least preliminarily, strongly indicate a dramatic difference in the level of changes in the brains of 60 high school athletes over the course a season, comparing those who wore the collar to those who did not.

As we all should know by now, the concern over long-term brain health does not stem solely, nor even primarily, from isolated yet powerful concussive blows, but rather more timid, but repetitive mild blows to the head, which an NFL player can sustain routinely in the area of four figures over the course of a year.

If there is indeed a legitimate finding here that can help players protect themselves from the effects of repeated blows to the head, then it would not be exaggeration to describe its impact as revolutionary to a greater extent than has been the HANS device in auto racing.

One of the arguments that has always dogged the proponents of player safety has been the fatalist argument from futility. Because there is no helmet that you can put in somebody’s head, there is not much you can truly ever do about protecting from brain injury.

This research could completely turn that fatalist argument on its head, with a virtual helmet of excess blood that helps to shield the brain from crashing into the cranial walls upon impact. Even if this is merely the stepping stone to something more significant, I feel that this provides the pathway to a potentially sustainable solution to a very serious problem.

The other reason that I find the research so fascinating is in part due to its inspiration and what it says about the nature of evolution. Evolution is a bottom-up process that works with existing parts, rather than a top-down process, and during the course of time, this has led to many illogically convoluted adaptations in the anatomy of animals across the spectrum, including the human anatomy.

That Bailes thought to draw inspiration from an animal uniquely adapted to banging its head and seeking to replicate that trait artificially through a simple device for those who must adapt to banging their own heads repeatedly is really quite clever.

I sincerely hope that, in time, something dramatic emerges from this research, and if indeed this simple collar is as effective in reducing the traumatic effects of repeated sloshing as preliminary research might indicate—there has yet to be any findings of negative effects from increasing the level of blood flow in the brain—then I sincerely hope that it finds its way into the status of standard sports equipment as soon as humanly possible.