By Alex Kozora

With training camp just hours away from beginning and preseason games soon to follow, there will be hours of film to pour over, picking out concepts and explaining why they did or didn’t work. As a preview, we’ll pick apart three concepts from each side of the ball that could be used most often, or be most effective, in 2014. Some are newer while others are already staples of the Pittsburgh Steelers.

For this article, three offensive concepts to keep a close eye on this year.

1. Outside Zone

No scheme has been given more airtime during the offseason than zone blocking. Since Mike Munchak’s hire, it’s been billed as the Steelers’ revival project. The team unsuccessfully failed to implement zone blocking last year, running less inside zone as the season wore on and virtually no outside zone.

With the return of Maurkice Pouncey, so can the outside zone.

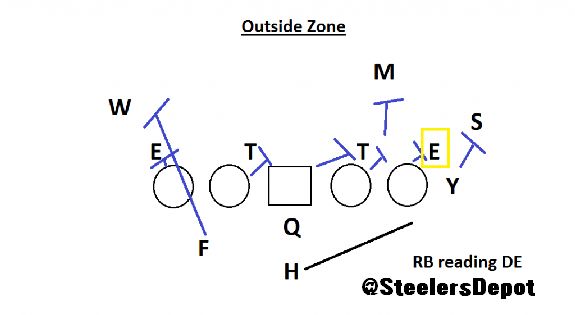

Zone blocking is a concept we’ve broken down during the summer film sessions. Focusing on outside zone, we’ll begin by breaking it into two categories: what the running back is looking for and how the offensive line blocks it.

Remember, zone blocking differs from power schemes because it doesn’t explicitly tell the running back which gap to run through. This isn’t “Lead Strong” with the running back following the fullback through the hole. Outside zone involves the running back running off tackle, his aiming point either to the outside hip of the tackle or the inside hip of the tight end, and then making a decision.

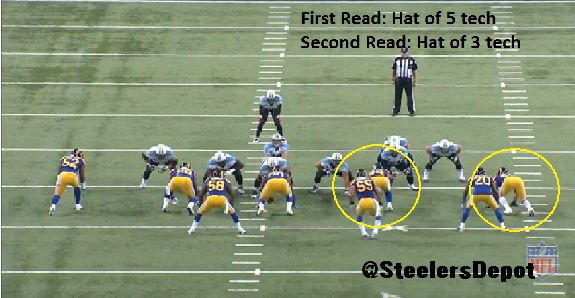

That decision is based off the direction of the defensive line’s helmets (hats, as it’s commonly referred to).

In outside zone, he’s reading the hat of the second defensive player to the direction the play is being run to. As an aside, shaded nose tackles don’t count as the first hat. So in a 3-4 defense, he’s reading the outside linebacker. In a 4-3, it’s the playside defensive end.

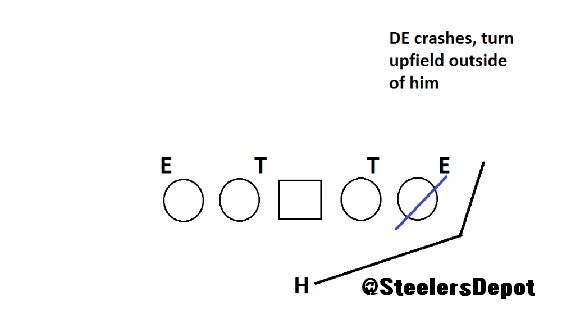

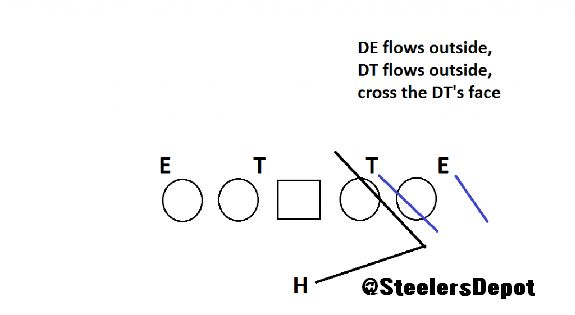

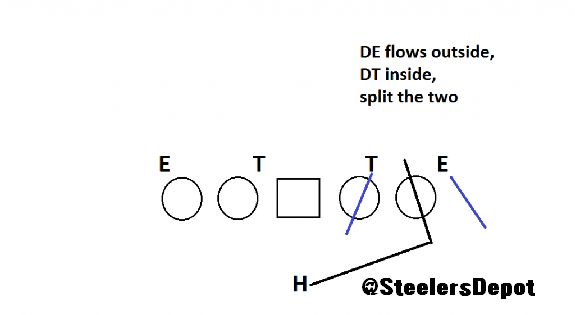

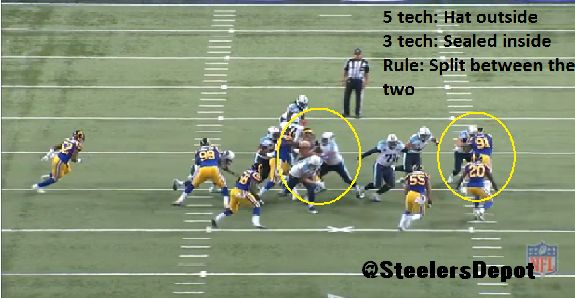

If the defender’s hat goes inside, the back turns upfield to the outside of him. If his hat goes outside, the back reads the lineman to the inside. If his hat also goes outside, the back cuts back across his face. If it goes inside, the runner splits the two defenders.

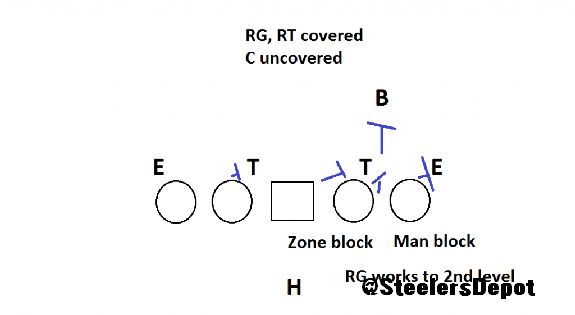

The lineman’s blocking rules are fairly universal, regardless of inside or outside zone. The blocking scheme is always envisioned from the playside. If a lineman is “covered”, meaning there’s a defensive lineman over top of him, he’ll base (man) block him.

Example: the team runs outside zone off right tackle. The tight end and right tackle are covered by the outside linebacker and defensive end, respectively. They will bucket step, opening their hips, to the right, and man block each, attempting to drive the defenders down the line. It’s not that dissimilar to a power scheme.

The difference is when the frontside lineman is covered and the backside lineman isn’t. This is where they zone block. The two lineman double-team, often with the frontside player moving to the second level to pick up a linebacker.

Example: same scenario, a team runs outside zone off right tackle. This time, the right guard is covered by the DT while the center is uncovered (no lineman shaded over him). The guard and center zone block, double-team, the tackle. Once the guard receives help from the center, he rips through the tackle with his backside arm (dip the inside shoulder), and moves to base block at the second level.

In short, it’s combination block. Chip the tackle, work to the next level when help arrives. Same principles across the board for the rest of the line. Very simple and easy to coach. It’s why teams love to run it.

Let’s see it in action. And we won’t use Pittsburgh as a guide. We’ll use Munchak’s old team – the Tennessee Titans. Best way to look at the future is to look at his past.

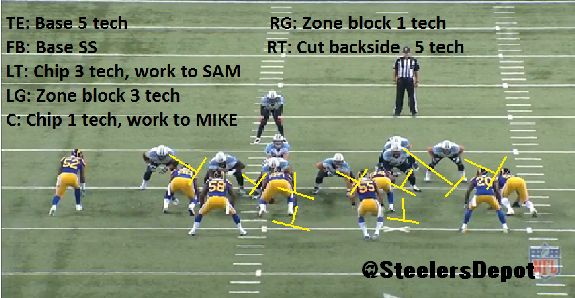

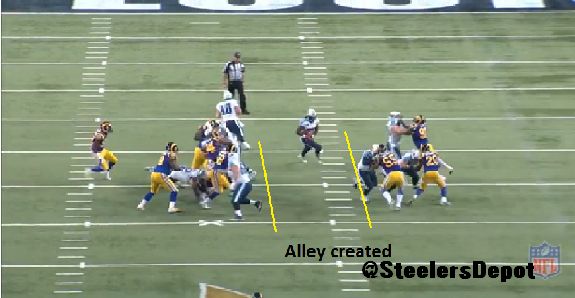

First run of the game for the Titans against the St. Louis Rams in Week Nine. Titans are in 21 personnel with the Rams playing their base 4-3, with a safety in the box. Outside zone is the call, running to the left tackle.

Going to our zone blocking principles, we know how the Titans plan to block it. The playside tight end base blocks the defensive end, #91 Robert Quinn. Since the left tackle is covered and the left guard is uncovered, they zone block. The left tackle chips then works to the second level while the left guard man blocks the three tech. The center and right guard do the same. The backside tackle attempts to cut the backside end.

Chris Johnson is reading Quinn’s hat. It stems outside, meaning he has to look back to the tackle to determine his lane. The tackle is sealed to the inside. Zone blocking tells us to split the two lineman and that’s what the runner does.

It’s blocked beautifully and opens up a huge lane for Johnson, picking up 23 yards on the play.

Outside zone won’t be run all the time. Plays that are lateral-dependent run the risk of getting blown up in the backfield if it isn’t blocked properly. But against aggressive one-gapping teams, it can be a huge weapon that will pay monster dividends.

2. Wheel Route

Here’s one that I haven’t mentioned much during the summer. It was a well the team went to often in 2013 despite its limited success. With the maturation of Le’Veon Bell, it could improve. And it’s an ideal route concept for a player like Dri Archer.

Not nearly as much analysis here as there is in breaking down zone blocking but that doesn’t mean it’s less effective. It’s a simple route concept. Begin by running to the flat, and when you’ve hopefully lured the defender into thinking it’s a quick throw, break and drive upfield on a fly pattern.

It was an idea that was likely born out of Bell’s receiving prowess. You don’t catch 45 passes by accident.

The concept came almost solely out of empty sets. Split Bell in the slot to the two receiver side, have the outside receiver run an in-breaking route to hold the corner, and run the back on the wheel.

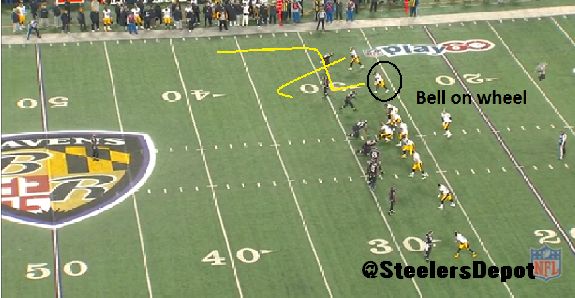

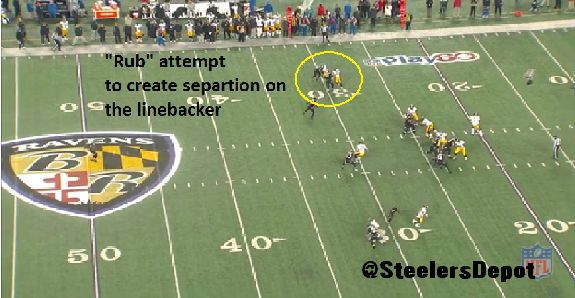

We see it here on 3rd and 2 late in the third quarter against the Baltimore Ravens.

With such an aggressive look by the Ravens, all but the deep safety are on or near the LOS, it’s a good counter. Put the running back one-on-one with the linebacker without the defender having any help over the top.

Bell’s flat is run underneath of Antonio Brown’s curl route, with the side effect of hoping to create a rub on the linebacker, allowing for that extra step of separation. Then turn upfield, playing it as if it were a fade.

Unfortunately, as was often the case on these attempts, the pass falls incomplete. Bell is an asset as a receiver, but he isn’t the fastest and doesn’t do a great job of naturally separating.

Enter Archer. He’s a guy who can get separation. His hands are inconsistent but his route running is above-average. Speed kills and he’s got a truckload full of it. This is how splash plays are born. Get the right look and take advantage of it. Think of a slow linebacker, a tired defense caught in the Steelers’ no-huddle, or even set the defense up by throwing to the flats out of that look first and then running the wheel to counter it. Running one play to set up another is something Todd Haley does very well. Against an aggressive linebacker, it’s tremendous bait.

A no-brainer use for Archer in his rookie year, and I’d bet good money you’ll see it a few times during the regular season.

3. Recognizing Tackle/End Stunts

This last one is about the offense reacting to what they see as opposed to creating it. But as I’ve harped on, it’s a huge area of concern for Pittsburgh. The problems in pass protection were as much mental as they were physical. Ideally, with more cohesion along the line, it will become less of an issue.

As I’ve shown before, these aren’t exotic, Dick LeBeau type blitzes. Just your basic twists with the end looping inside over the tackle. And they carved the Steelers’ line into pieces in 2013.

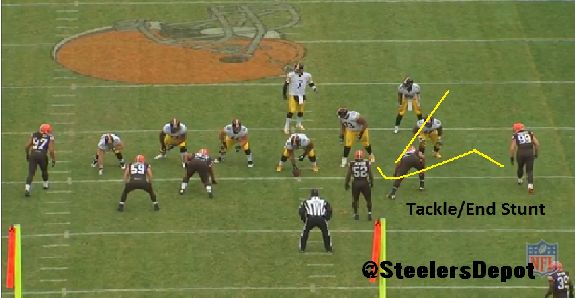

There are a hundred examples to choose from, I’ve shown a couple throughout my “48 Play” series, but a new one that came against the Cleveland Browns in Week 12.

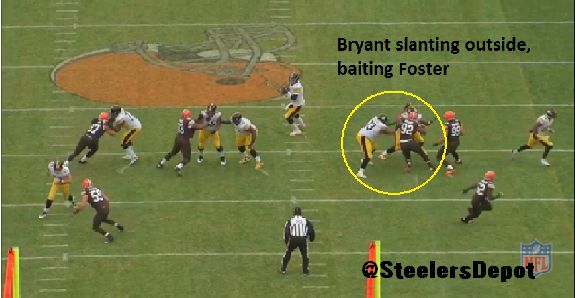

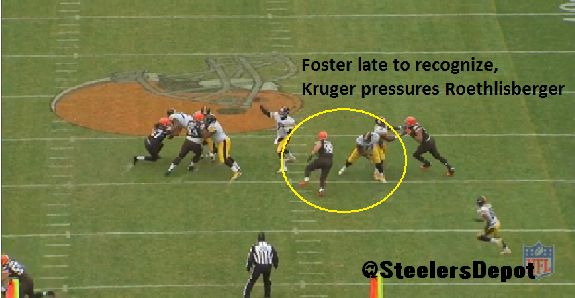

Tackle/end stunt from the weakside tackle and end, Desmond Bryant and Paul Kruger. Again, nothing fancy from the Browns. Bryant slants outside into the tackle while Kruger rushes over the top and to the inside.

Ramon Foster takes the bait and follows Bryant for too long. He’s too late to recover once he sees Kruger on the stunt and isn’t agile enough laterally to get in front. Kruger gets a free shot on Ben Roethlisberger.

The pass is still completed and Roethlisberger luckily avoids being taken to the ground, but it’s another blemish on the offensive line. By my count, eight of the team’s 42 sacks came from blatantly missed stunts like this one. Who knows how many pressures.

Clean that up and life for your franchise quarterback will be a lot cleaner.

Other concepts to keep in mind: G-Lead, TE combination blocks out of 12 personnel, fold blocks, packaged plays