John Bain “Jock” Sutherland led the Steelers to their first playoff game in franchise history. A legendary coach, Jock never experienced a losing season in his 20-year college coaching career and four as an NFL head coach. The worst record he recorded was his first as Steelers’ head coach, when they finished 5-5-1 in 1946.

MAN OF MYSTERY

Jock Sutherland was born in Scotland. Many legendary figures have mystique in their lives, and Sutherland is no different. One question is exactly how old he was. Most sources record his birthdate as March 21, 1889. Yet, Sutherland listed his date of birth as March 21, 1888 on his World War I draft registration. Jock listed his date of birth as March 21, 1889 on his World War II draft registration. Jock listed his date of birth as March 21, 1888 on his 1917 petition for naturalization.

Similarly, it is hard to pin down exactly when Jock Sutherland arrived in the United States for the first time. Different records provide different dates. The 1930 US census record shows his immigration year as 1909, but the original record shows 1907 crossed out and replaced by 1909. Immigration records certify his arrival to the United States as August 1909 on board the Columbia, an Anchor Line ship which was a Scottish merchant shipping company. Oddly, John Sutherland shows up on a passenger manifest of the SS Furnessia, another Anchor Line Ship, that sailed from Glasgow on April 10, 1909. However, he is stamped as a “non-immigrant alien.”

I rely on Harry G. Scott’s biography called Jock Sutherland: Architect of Men for a lot of information on the legendary coach. Scott talked to many of Jock’s former players, fellow coaches, and Sutherland family members for firsthand accounts. I also used newspaper.com to read contemporary reports of Sutherland. The book contains many details of his amazing life, and I encourage anyone interested in Steelers or Pitt football history to read a copy.

EARLY LIFE

John Bain Sutherland came into this world on or about March 21, 1889 at 9 Carlton Street, Coupar Angus. His father, Archibald, died, leaving John’s mother a widow with five children. His father was trying to lift a girder off a workman that he was trying to save in a work accident. He died of internal injuries. His mother was deeply religious and had high expectations of her children. Both the discipline and faith were imbued on Jock, which he carried throughout his life. Sutherland was large for his age, and as a youngster amused himself by picking up large rocks and heaving them as far as he could. Really not very unusual for the place and time, as the “stone put” (think shotput) is one of the events of the Scottish Highland games.

John Sutherland started work at age eight as a “loon” (light farm worker). He caddied for golfers from age 11 until 15. A golfer helped him get a higher-paying job, and he left home at 15 to porter at a train station outside Glasgow. Always athletic, Sutherland played soccer on the Glasgow train station team.

COMING TO AMERICA

Meanwhile, his older brother Archie moved to Canada to work on farm. Archie then moved to Pittsburgh to join a friend as an attendant at the Dixmont Mental Hospital. John departed Scotland and arrived in the USA in 1907 on the SS Columbia, aged 18.

He worked at Dixmont mental hospital with his brother. This is where coworkers nicknamed him Jock. Sutherland played soccer in Ambridge. Sewickley hired him as a cop because of his size. Sutherland excelled on the Sewickley YMCA track and field team. His specialty was the field events, where all the stone throwing as a child paid off in both his strength and technique.

MAN AMONG BOYS

Lou McMaster, a friend, enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh, and encouraged Sutherland to join him. However, he only had a grade school education, and with the help of mentors from the YMCA he entered Oberlin Academy in the fall of 1913 at age 24. He was a man amongst boys, and it showed on the athletic fields. But the discipline instilled by his mother translated into academic success, and by the summer of 1914 he was in the Pitt dental school and attending the Pitt football training camp on the recommendation of McMaster. The coach loved his size and athleticism.

ALL-AMERICAN ATHLETE

As an athlete, Jock earned varsity letters in three sports at Pitt: Wrestling, track, football. He also boxed in the Mid-Atlantic AAU Championship. Sutherland won the championship by knockout over a much more experienced fighter who was turning pro. He wrestled on Pitt’s first intercollegiate wrestling team. Heaving stones as kid helped him in track field events. At the 1917 Penn Relays, he threw the discus and hammer throw. He helped Pitt place second in the 1918 IC4A, a forerunner of the NCAA annual track meet. His first coach, Joseph Duff, left after one season and was killed during World War I. Another coaching legend, Glenn “Pop” Warner, coached him the next three seasons. In 1916, 32,000 fans came to Forbes Field to watch Pitt defeat the University of Pennsylvania in a 20-0 win. In his four seasons at Pitt, the Panthers rolled to a 33-1 record. Washington & Jefferson handed the Panther their only loss. Sutherland was named an All-American guard in 1917 by Jack Veiock of the International News Service. Sutherland was named to the first all-time Pitt football team in 1930. Quite a college career.

WAR PRESENTS COACHING OPPORTUNITY

The world was at war while Sutherland attended college. He was naturalized a US Citizen on September 10, 1917 and enlisted in the army reserve December 1917 at age 28. He was in a medical officer training camp named Camp Greenleaf, located on the Chickamauga National Battlefield Park. The camp sponsored a military service team, and despite being in training took over from the original coach for his first football experience as a player-coach. The Camp Greenleaf team was undefeated and capped their season at a high-profile game in Washington D.C. in front of a lot of military officials and football fans including college coaches. Camp Greenleaf defeated Camp Dix, New Jersey, 34-0.

The war ended before he was deployed, and he was discharged at the end of 1918. In 1919, Sutherland played one season for the Massillon Tigers, including a game against Jim Thorpe and the rival Canton Bulldogs one year before the NFL started. He had a strong game stopping Thorpe on defense.

COACHING OR DENISTRY?

Sutherland became a dental teacher at Pitt with the intention of starting own dental practice. But his success with the Camp Greenleaf team was noticed by the college football world. Stanford, Iowa, and Lafayette offered Sutherland head coach positions. He chose Lafayette to remain in Pennsylvania, and continued teaching at Pitt between seasons.

Jock took over a program that experienced losing seasons the previous three years. He quickly transformed them into a national power. Instilling discipline and arduous work, he improved a mediocre squad that recorded a cumulative 6-9 record in the two prior seasons. Sutherland developed the team into a winner, going 6-2 his first season at the helm. He recruited players from nearby Easton High School and drilled them on his system of play. He emphasized execution on designed plays, much like Vince Lombardi worked to perfect the famous Packer sweep by repetitive drilling until the players had it down pat.

LAFAYETTE, I AM HERE

Sutherland recruited Frank “Dutch” Schwab, who was an anchor at guard on his teams. Schwab was twice named an All-American by Walter Camp. Graduating from high school at 14, he worked in the coal mines, then served as a sergeant in World War I. He played on a service team, and Sutherland convinced him to attend college. He played in the first four of Sutherland’s years as coach of Lafayette. Schwab noted that “Jock was a very much misunderstood man. He may have seemed cold and unfeeling, but he had a deep and warm feeling for his players and followed their careers with a sympathetic and real interest…. I owe my education, and whatever honors I received in football, to Jock Sutherland.”

The team slipped to 5-3-1 in 1920. Sutherland considered it the poorest experience during his time at Lafayette. Although a young team with four freshmen starters, they lost 12-7 to Navy and then a 7-0 loss to Penn. The other blemish was a 14-0 loss to his alma mater Pitt. They did finish the season on a high note, beating Villanova 34-0 and then Lehigh 27-7, their second consecutive win over their archrival.

NATIONAL ATTENTION

In 1921 with the nucleus of the team intact, the Leopards opened with a 48-0 win over Muhlenberg and then avenged the loss to Pitt the previous year, winning 6-0. The traditional season finale against Lehigh was a 28-6 victory. Lafayette scored 274 points while giving up just 26 in a nine-game undefeated season. They were one of several teams considered to be collegiate national champions. Lafayette entertained the possibility of a postseason game out west, but the school’s athletic committee with Sutherland’s support declined. This was the same season that tiny Washington & Jefferson played in the Rose bowl after going 10-0-1, and played the Cal Golden Bears to a 0-0 tie after traveling with only 12 players to play the game. Who knows, Sutherland’s Lafayette team may have traveled in their place if not deciding to forgo postseason play.

The 1922 team jumped out to a 5-0 start, but lost to Washington & Jefferson 14-13, blowing a 13-0 first half lead, a missed extra point the difference in the game. Lafayette won the remaining games except their last game, dropping a 13-7 contest to Georgetown. In his final year coaching Lafayette, the team went 6-1-2. He may have continued coaching at Lafayette, but his former coach at Pitt, Pop Warner, left Pitt for Stanford.

SWAPPING LEGENDS

Jock Sutherland was taking over a program from a legend. Pop Warner had already coached 27 years including the Carlisle teams led by the play of Jim Thorpe. In his nine years at the helm, Pop coached Pitt to a 60-12-4 record, including four undefeated seasons. Warner helped develop 15 consensus All-Americans, including eight at Pitt up to that point. Jim Thorpe (1911 and 1912) and Sutherland were among the 15 All-Americans according to the College Football Sports Reference. Pop would develop five more consensus All-Americans during his nine years at the helm with Stanford. Big shoes to fill, but contemporary Pittsburgh newspaper accounts were excited at the prospects of Sutherland as a suitable replacement following his success at Lafayette.

In his 15 years as Pitt’s head coach, Sutherland would lead the Panthers to a 111-20-12 record with four Rose Bowl trips and 13 All-Americans. A 14th, Frank Schwab, was a two-time All-American at Lafayette. Warner and Sutherland split eight of the nine national championships claimed by the Pitt Panthers. Warner won with his 1915, 1916, and 1918 teams that Jock Sutherland played on, Sutherland-coached teams won five, including the 1929, 1931, 1934, 1936 and 1937 teams.

For comparison, Joe Paterno developed 30 consensus All-Americans and two claimed and three unclaimed national championship titles in 46 years at Penn State. Paul “Bear” Bryant coached 21 All-Americans during his 38 years as a head coach at four schools, and six national titles at Alabama.

END OF AN ERA

Sutherland may have gone to greater heights at Pitt, but his run ended abruptly. University of Pittsburgh Chancellor John G. Bowman addressed the College Physical Education Association in December 1938 saying, “It is no sin to pay a boy to go to college, but that it is a sin… to pay him… to play a sport for that college.” A backdrop of Chancellor Bowman’s remarks were discussions with the Western Conference forerunner of the Big Ten Conference.

The Pittsburgh-Post Gazette’s front page headline blared, “Sutherland Tenders Resignation to Pitt” on March 6, 1939. Trouble brewed for several seasons. Articles pointed to a dispute between the athletic director and Sutherland over the amount of spending money for the players who won the 1937 Rose Bowl over Washington. That athletic director resigned, but his successor and Chancellor Bowman continued to press the football program with “Code Bowman,” which he instituted to de-emphasize athletics at Pitt, including athletic scholarships.

The administration of the code is what ultimately led to Sutherland’s resignation. Sutherland said the team could move forward if they played lesser competition if he couldn’t lure recruits with scholarships and other incentives. The school refused because they wanted to continue playing top football programs to ensure high gate receipts at Pitt Stadium. Pitt hosted several games with over 70,000 fans filling Pitt stadium during Jock’s tenure. The Pitt Football team managed a 5-4 season the year after Jock’s resignation, but then suffered eight straight losing seasons until achieving a 6-3 record in 1948, ironically the year of Jock’s death.

Please read When Pitt Ruled the Gridiron by David Finoli for more details on Pitt’s football glory days, when the Panthers laid claim to five national championships between 1929 to 1937.

JUMP FROM COLLEGE TO THE PROS

Sutherland as a legendary coach was in demand. He took a year off except to coach the Eastern College All-Stars against the NFL champion New York Giants. In 1940, Jock became one of the first high-profile college coaches to jump to the NFL. Brooklyn Dodgers owner Dan Topping won the sweepstakes for Sutherland’s services by signing him to a three-year contract. The Dodgers enjoyed only two winning seasons in their ten years before Jock took the reins. The Dodgers finished 4-6-1 in 1939. Jock transitioned from college to professional football coaching seamlessly.

In his first year, the team went 8-3 and earned a second-place finish in their division. In 1941, the Dodgers slipped to 7-4 but still placed second in the division. The Pittsburgh Steelers’ only win that season was 14-7 over the Dodgers. With two wins over the first place Giants, the Dodgers would have won the division and a berth in the NFL championship if they had not faltered against Pittsburgh.

The Dodgers were playing their season finale against the New York Giants on December 7, 1941 when the loudspeaker started paging Colonel Donovan during the game. Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor and Washington tracked down Colonel “Wild Bill” Donovan, President Roosevelt’s intelligence coordinator attending the football game, to inform him of the sneak attack.

BACK IN SERVICE

Sutherland still had one year remaining on his contract with Brooklyn. Jock at 52 years old already volunteered to serve during the first World War. Sutherland was making $18,000 a year plus a cut of the gate receipts. The Navy would pay him $361 a month. He of course attempted to enlist to serve during the second World War, but was rejected based on his age and eyesight. Jock continued to pursue it, not reading anything but large script on a blackboard for six months. He finally passed the eyesight test and the Navy issued him an age waiver. Jock Sutherland was commissioned a Lieutenant Commander on July 11, 1942. With his background in teaching and coaching, the Navy assigned Sutherland to the Bureau of Naval Personnel, Training Division.

He spent the war years in the United States setting up Naval Rest Centers, providing a place for sailors to rest and recuperate for their next assignment. He was released from active duty on November 24, 1945 after hostilities ceased. But the Army requested Jock to travel to Japan to help coach a military football team for the “Pacific Olympic Games” for the military forces still in theater. He spent the first part of 1946 in Japan before returning to Pittsburgh.

FOOTBALL MACHINATIONS

In the last year of the war, Art Rooney and Bert Bell delayed announcing the new coaching staff for the 1945 season. Old reliable Walt Kiesling resigned and joined the Green Bay Packers in late January. Several rumors in newspaper articles including a merger with the Cleveland Rams, and that the Steelers were courting Sutherland may have led to the delay and Kiesling’s departure. Finally, Rooney and Bell announced that Jim Leonard would coach the Steelers in 1945 on April 22. A Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article in July 1945 opined that the appointment was for one season only, as the Steelers still wanted Jock Sutherland once the war ended.

The creation of the All-America Football Conference in June 1944 resulted in several events that opened the way for Jock Sutherland to coach the Pittsburgh Steelers. First a squabble between the Brooklyn Dodgers owner Dan Topping and New York Giants owner John Mara over the Dodgers moving their games to Yankees Stadium ended with Topping moving his team to the upstart league. This ended any potential issues with the unfulfilled third year of Sutherland’s contract with the Dodgers. The creation of the Cleveland Browns hastened the NFL Rams to move from Cleveland to California, ending any potential merger talks with the Steelers.

NFL owners fired commissioner Elmer Layden, replacing him with Steelers’ co-owner Bert Bell. Bell sold a large part of his 50% share of the team to Barney McGinley, whose son Jack remains a part-owner to this day. The balance went back to Rooney. Negotiations between Sutherland and Bert Bell included an option to buy some of Bell’s shares of the team and a percentage of the team profits. Signed before he left for Japan, the five-year contract was praised widely as a new beginning for the Pittsburgh Steelers franchise.

THE GREAT SCOT HOPE

Sutherland became the ninth coach in the Steelers’ 14-year existence; 11th coach if we include the two merger seasons with the Philadelphia Eagles and Chicago Cardinals. In 13 prior seasons of play, the Steelers managed three non-losing seasons. In 1936, the Steelers went 6-6 under Joe Bach. Walt Kiesling led the Steelers to 7-4 in 1942, the Steelers’ first winning season. The 1943 Steagles co-coached by Greasy Neale and Kiesling managed a 5-4-1 record. But then the merger with the Cardinals led to a disastrous 0-10 record. The following year interim coach Jim Leonard got the Steelers to 2-8, while former partner Cardinals finished 1-9 but would soon reverse their fortunes.

Jock intended to rebuild the Steelers from the ground up. He attended several games in the 1945 season and told reporters after signing his contract that, “Frankly, I couldn’t win with the squad which ended the past season.” In 1945, 49 different players played in at least one game. Part of the reason for this roster churn were veterans such as Bullet Bill Dudley returning midseason to civilian life from the war. The NFL limited gameday rosters to 33 players in 1945 and 1946. Sutherland kept only eight players from the 1945 team, but that included Bill Dudley and aging Chuck Cherundolo. Four of six players who started more than seven games for the Steelers in 1945 were gone. But Sutherland brought stability. In 1945, 49 players appeared on gameday rosters. In 1946 under Jock, it was only 34.

JOCK KNOWS BEST

Sutherland was not afraid of using young players. Nineteen of 34 Steelers that appeared in at least one game were rookies. With 11 regular starters, six rookies started seven or more of the regular season games. As for the scheme, reporters asked Sutherland if he intended to use the T formation, which the Steelers briefly experienced when merged with the Eagles and Cardinals in 1943 and 1944. Sutherland stated flatly that, “I intend to use the system I know best.” That system was the single wing. After all, he experienced winning seasons in all 22 seasons he was a head coach, including two in the NFL. Sutherland intended to win with a ball control ground offense and a stifling defense.

In 1946, 72% of the Steelers’ offensive plays were rushing attempts, compared to the league average of 64%. Only the Green Bay Packers averaged more runs per offensive play. But the Steelers had the least turnovers, giving the ball up just 28 times compared to the league average of 39.8 in the 1946 season. Pittsburgh’s scoring was dead last in the league, averaging just 12.4 points a game. But their defense was even more stifling, allowing opponents just 10.6 points per game, the league’s stingiest defense.

Bill Dudley was the team’s star. A first team All-Pro for the Steelers before he entered military service, Dudley completed 1946 leading the league with 604 rushing yards in 11 games and was the best punt returner, averaging 14.3 yards on 27 returns. On defense, he led the NFL with 10 interceptions and 242 interception return yards, including a pick six. Dudley also place-kicked, making 12 of 14 extra points and two of seven field goal attempts. Amazingly, he did not make the Pro Bowl that year, although he won the Joe F. Carr Trophy as the NFL’s MVP.

LOSS OF A STAR

In 1946, the Steelers were 5-3-1 with two games remaining, but dropped a 7-0 decision to Eastern Division winner New York Giants and then a 10-7 loss to the Philadelphia Eagles to finish the season 5-5-1, the worst season of any Jock Sutherland-coached team. Pittsburgh fans were optimistic despite a mediocre record. The Steelers were competitive in every game and the fans were flocking to the stadium. The fanbase sensed that Pittsburgh was on the verge of consistent winning football.

Bill Dudley’s announced retirement then trade to the Detroit Lions tempered Steelers followers’ enthusiasm between the 1946 and 1947 seasons. Rumors had emerged of dissension between Dudley and Jock in the preseason. Dudley hurt his knee in the final three minutes in the 1946 finale against the Philadelphia Eagles. By January, Dudley said his body could not take the pounding and agreed to coach the backfield of his alma mater University of Virginia. Rooney had offered to increase Dudley’s pay but was rebuffed. Rumors continued to circulate, including a scheme where Dudley would coach at Virginia during the week but play for the Steelers on the weekends.

But Dudley made it clear he did not intend to play in Pittsburgh, though denying a rift with Sutherland. The Steelers received a first round draft pick and three halfbacks from the Detroit Lions, who offered Dudley somewhere between $20-24,000. Ironically, that draft pick went from the Steelers to the Chicago Bears, who used it to pick quarterback Bobby Layne. After playing one year in Chicago, Layne would go on to glory with the Detroit Lions, winning three championships before finishing his career in Pittsburgh. If the Steelers had only held onto that draft pick!

PLAYOFF!

In 1947, the Steelers signed Johnny Clement as a replacement for Dudley, along with 15 rookies. Clement finished second in the league with 670 rushing yards and was among the league’s passing leaders. The Steelers were 7-3 with two games to play in 1947. Unfortunately, they lost 21-0 to the Eagles, a team the Steelers beat 35-24 just weeks before. The significant difference was the absence of Johnny Clement, who suffered an injured elbow. Pittsburgh finished the regular season at 8-4 by beating Boston 17-7. This put the Steelers in a tie with the Eagles for first place. Pittsburgh and Philadelphia needed a playoff game to determine who would represent the East Division against the West Division champion Chicago Cardinals for the NFL championship.

Clement was back for the playoff game against the Eagles, but although the game’s leading ground gainer, he had only 59 yards, and the Eagles defense and his elbow held him to four completions on 16 passing attempts. Former Steeler Tommy Thompson masterfully led the Eagles T-formation, completing 11 of 17 passes including two touchdowns. A touchdown on a punt return in the third quarter iced the game.

Still, Sutherland had led the Steelers to an 8-4 record and a playoff game! For more details on the 1947 season including the rift between Jock Sutherland and Bill Dudley read Starless: The 1947 Pittsburgh Steelers by Steve Massey.

The consensus of most pundits was Jock Sutherland’s coaching job in 1947 “was one of the best coaching jobs of the year.” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported the Steelers’ 1948 prospects as “Team should be stronger and will be in the running for the title all the way; a year’s added experience under the Sutherland system will help the new men to be even better …” But sadly, it was not to be.

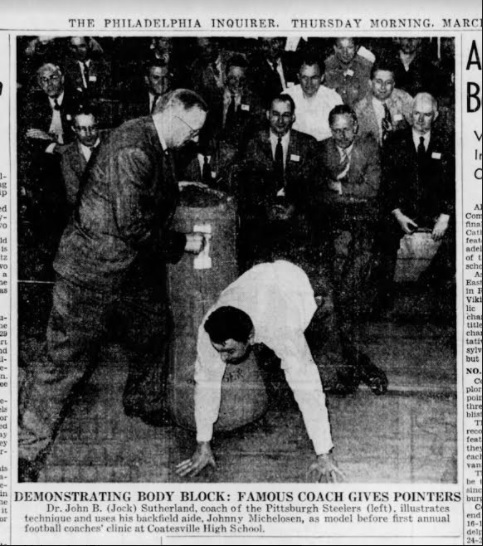

I’M JOCK SUTHERLAND

In March 1948, Jock Sutherland postponed a scouting trip by two weeks to conduct a football coaches’ clinic at Coatesville High School. Sutherland had experienced headaches, and his sister asked him to return to Pittsburgh for a check-up. Always dedicated to the job, Sutherland drove south on March 25 instead to meet his commitments to find talent for the Pittsburgh Steelers. He visited Duke University and Wake Forest. His last known location was New Orleans, as he kept regular contact with the Steelers front office.

On April 7, 1948, a milkman encountered a man walking down the road with a suitcase and offered him a ride. His car was in a ditch near Bandana, Kentucky, nearly 600 miles from New Orleans. The milkman noticed that the man was noticeably quiet, so took him to the local sheriff. The man announced, “I’m Jock Sutherland.” But little more. His driver’s license confirmed his identity, and he was transported to the nearest hospital, located at Cairo, Illinois. Initially, he was diagnosed with exhaustion, dehydration, and amnesia.

Assistant coach Johnny Michelosen flew with others to pick Sutherland up and return him to Pittsburgh for a full check-up at the West Penn Hospital. Jock recognized friends, sister, and co-workers. He did have his memory but was in obvious extreme distress. The examination revealed a large brain tumor that was exerting tremendous pressure, hence his frequent headaches. Jock and his family took the only option available. In Jock’s words in a lucid moment that Saturday, “They’ve got to operate. I’d be no good like this.” The operation determined that the tumor was malignant and so deep and scattered that removal was impossible. Jock Sutherland never regained consciousness, and passed away early on Sunday April 11, 1948.

EPITHET

Jock Sutherland may be misunderstood by many. He tended to be quiet and unexpressive, but it is evident from the many testimonials he deeply cared for people. He is often thought of as old-fashioned, since he refused to give up on the single wing. But he was also known to be innovative with that offense, and utilized misdirection as well as anyone on opponents he would deeply scout. Jock pushed the Steelers to favor the draft over veteran players that later Steelers coaches reversed, but was reinstituted by Dan Rooney and Chuck Noll.

Recently, I was chatting to a young Steelers fan and mentioned my work on this article. Zach said, “I know who he is! I lived in Sutherland Hall at Pitt for a year.” Very nice that his legacy lives on.

Many, many persons both famous and unknown paid tribute to Jock Sutherland. Here is a memorial poem written by James R. Whittet, a childhood friend from Coupar Angus:

A sterling man, a decent sort,

And skilled in every manly sport;

Now Jock he always played the game,

And trained his team to do the same.

As a coach there was none better,

He did the job just to the letter;

Fame and fortune was his lot,

And honours plenty came unsought.

Both on the field and in the street,

A better lad you could not meet;

With modest mien and humble grace –

A credit to the Scottish race.

A faithful friend, a loving son,

His warfare’s o’er, his duty done;

To sisters and Mother left behind

Give strength, O God, and peace of mind.

At a tribute dinner that included 1,400 guests a few weeks after his resignation at Pitt in 1939, Jock Sutherland’s own closing remarks are a suitable epitaph:

“I have tried hard to give back part of what I have owed to Pittsburgh since I came to this city as a youth, from a village in Scotland, and found here teachers and good friends to guide me on my way. I shall not say good-bye, but rather good night and God bless you.”

YOUR SONG SELECTION

I always like to include a song. Here are two that mix tradition with modernity. First is a military tattoo by the International Massed Band (bagpipes & drums). The second is A Mix of Shipping Up to Boston and Enter Sandman by three female pipers: One from Scotland, one from USA and one from India.