The injury bug bit again on Sunday night at Heinz Field. Pittsburgh Steelers WR Antonio Brown bobbled a pass in the end zone and was briefly sandwiched between two New England Patriots defenders. In the traffic, Brown took a hit to his left lower leg and had to be assisted off the field. Although he was able to walk to the locker room, he was done for the night and probably for the next few weeks.

Initial reports called it a calf injury, implying that the Xrays done immediately did not show any fractures (broken bones). Concern arose when during the third quarter it was announced that Brown had been taken to the hospital for further evaluation. Twitter exploded and Steelers fans had a hideous sense of déjà vu from a couple weeks ago, when a similar report was made about LB Ryan Shazier. Going to the hospital rather than showing up on the sideline in street clothes is an omen of a more serious injury.

This time, the Steelers got lucky. Later reports revealed that the star wideout had sustained a calf muscle tear and that no surgery was needed. This came from both Ian Rapoport and Adam Schefter:

After a variety of tests, #Steelers WR Antonio Brown has a partially torn calf muscle, source said. The hope is that he’s OK for the postseason. His regular season is over. No surgery needed.

— Ian Rapoport (@RapSheet) December 18, 2017

Steelers WR Antonio Brown has a partially torn calf muscle, per source. Unlikely to play next week but expected back for the postseason.

— Adam Schefter (@AdamSchefter) December 18, 2017

So what was all the excitement about? And more importantly, WHEN CAN AB COME BACK AND PLAY?!!!

Hold that thought for just a sec while we do a quick anatomy review.

CALF MUSCLE ANATOMY

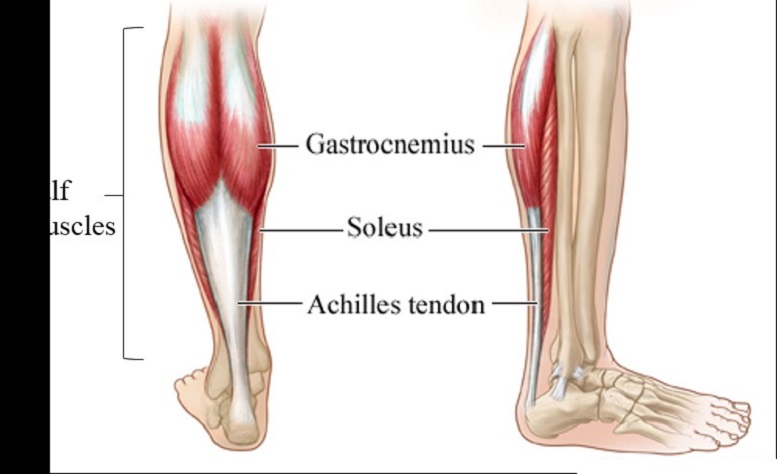

There are actually two muscles that make up the calf muscle: the gastrocnemius and the soleus. The gastrocnemius is the 2-headed muscle that forms the bulge on the back of the lower leg and has two heads. The soleus is smaller and flatter and lies deep to the gastrocnemius.

Figure 1 www.thedorsiflex.com

The two muscles join together at the lower aspect and are attached to the heel bone by the Achilles tendon, a strong heavy tendon that runs up the back of the ankle. The calf muscles work to pull the heel forward to allow movement for walking, running, and jumping…all things that are important for a wide receiver.

CALF MUSCLE INJURY

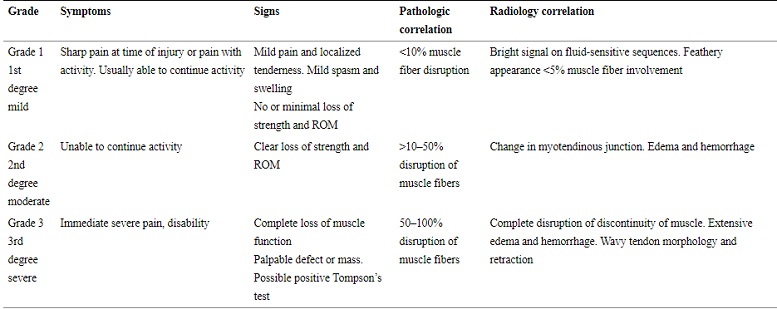

Like many musculoskeletal injuries, calf muscle injuries are graded on a scale of 1-3 by severity. Here is the breakdown from a paper in Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine:

Although Brown hopped off the field without putting any weight on his left leg, he was soon walking gingerly and was able to go down the stairs to the locker room without help. Based on that, he most likely has a Grade 2 injury, with 10-50% disruption of his muscle fibers. While the paper discusses a thorough technique to determine which muscle is injured by physical exam, MRI is still the most accurate and easiest way to define the injury, and Brown has almost certainly already had one last night.

So why the rush to the hospital? It is possible that the doctors and trainers were concerned about a possible compartment syndrome. During the game, Dr. Mark Adickes (@jocktodoc) posted a nice 2 ½ minute video explaining compartment syndrome very nicely.

The big news of Week 15 has been Antonio Brown’s injury. @JockToDoc has been all over the medical updates all day. Here is a behind the scenes look at Dr. Mark Adickes doing what he does best #FantasyZone pic.twitter.com/jyqIJ1Ihz3

— Red Zone Channel (@RedZoneChannel) December 17, 2017

COMPARTMENT SYNDROME

From the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons:

Compartment syndrome is a painful condition that occurs when pressure within the muscles builds to dangerous levels. This pressure can decrease blood flow, which prevents nourishment and oxygen from reaching nerve and muscle cells.

Compartment syndrome can be either acute or chronic.

Acute compartment syndrome is a medical emergency. It is usually caused by a severe injury. Without treatment, it can lead to permanent muscle damage.

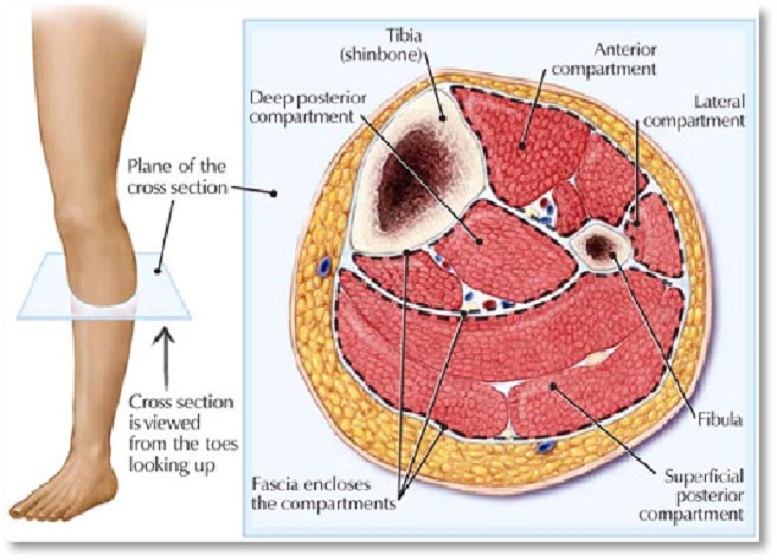

Here are the compartments of the calf, defined by sheets of strong fibrous tissue (fascia) that separate the compartments:

Figure 2 www.kingsleyphysio.com

When muscle fibers tear, they can bleed until the pressure of the compartment causes it to stop due to the pressure that builds. That pressure helps to stop the bleeding, but it can also impact blood flow through the area due to intense swelling. This was one of the problems that Bears TE Zach Miler had and what made his injury so serious.

When AB walked off the field to go to the locker room, his left calf was easily visible, and there was no obvious swelling. What that tells us is that there was no rapid bleeding which would cause a rapidly expanding hematoma, or collection of blood. What is doesn’t tell us is if there is pressure building in one of the deeper compartments. That is probably why he was rushed to the hospital.

From a clinical standpoint, compartment syndrome is diagnosed by the “4 Ps” (not to be confused with the Killer Bs):

- Pain

- Paresthesia (loss of sensation)

- Paralysis/paresis (loss of motor function)

- Pallor (which indicates lack of blood flow)

The diagnosis is confirmed by using a needle to measure the pressure in each compartment. The decision on whether surgery is needed depends on how high the pressure is compared to normal. If the pressure is high enough that it puts the blood flow and muscle at risk, a fasciotomy is done, cutting the different sheets of fibrous tissue longitudinal direction to release the tension in the compartment. I would post a photo of a leg with a fasciotomy, but I’m sure I’d get yelled at in the comment section. Click at your own risk here.

Fortunately, Brown did not have a compartment syndrome and did not require surgery. So let’s get back to what matters…

RECOVERY FROM CALF MUSCLE INJURY

We’ve already seen widespread reports from all the twitter doctors that Brown is down for the regular season and will hopefully return for the playoffs. The good news? I actually have scientific data to support what we desperately need to be true.

There isn’t much to do with a calf muscle injury but supportive care (rest, ice, massage, etc.) and let it heal. Scar tissue is our friend, and will help bind the muscle fibers together, recreating the strength the muscle had before.

Dr. Scott Rodeo, at the Hospital for Special Surgery in NYC (the ultimate ortho hospital) looked at calf injuries in NFL players from 2003-2015 for a single NFL team and published it in The Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. They identified 27 calf injuries in 24 players. 74% were isolated gastroc injuries, 15% were isolated soleus injuries, and 11% involved both muscles. The mean time to return to play for all injuries was 17.4 days (+/- 14.6 days).

Obviously, players with Grade 1 injuries will return sooner than players with Grade 2 or 3 injuries. And the position played is certainly a factor. In 2014, Green Bay Packers QB Aaron Rodgers never missed a game despite a calf muscle tear, leading his team to the NFC Championship. It was the Seattle Seahawks that kept him from the Superbowl, not his leg. Then again, Buffalo Bills WR Sammy Watkins had a tougher road back from his calf tear in 2015. He returned after 3 weeks (missing 2 games), only to reaggravate the injury and miss another month. And I’m sure true Steelers fans will remember Troy Polamalu going down with a calf muscle tear in the 2012 season opener. He missed 2 more games, practiced fully for a week and returned, only to get injured again. He claims it was a different muscle that kept him out for almost 2 more months. Then again, his initial injury was possibly a Grade 3 tear – he had horrible swelling and bruising for weeks.

PREDICTING BROWN’S RETURN

Antonio Brown is in a class by himself when it comes to work ethic and dedication. And just this morning, he tweeted that this injury is only a minor setback and he will be back:

even in adversity I can’t help but feel blessed. Thanks to everyone who reached out. This is a minor setback for me but not this team. The goal is still the same & I’m confident that we can & will achieve it. We may not have won the game yesterday but this TEAM made a statement. pic.twitter.com/L2drCGim2W

— Antonio Brown (@AB84) December 18, 2017

If the Steelers can take care of business, win out and secure a bye week, I feel confident that Brown will play to his usual unbelievable level in their first playoff game in the Divisional Round. If the Steelers fall to the 3 seed and have to play in the Wild Card round, there is still a very good chance that they will have AB back in good form, but he will run the risk of re-injury. Even in that scenario, he will certainly play. While there is short-term risk of aggravating the injury, there is no risk of long-term damage. As we all know, when it comes to playoffs, there is no tomorrow. Unless you win.