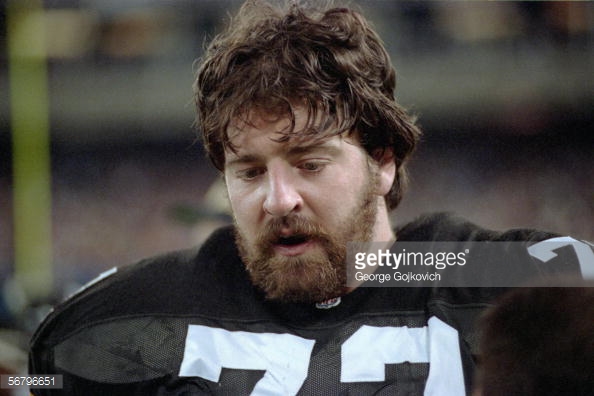

Had it not been for the way that his life ended, former Pittsburgh Steelers offensive tackle Justin Strzelczyk almost assuredly would not be nearly as well-known today as he is, such that he is remembered at all casually. His life is primarily discussed in the context of his death.

Strzelczyk, who played for the Steelers all throughout the 1990s, starting 75 of 133 career games, was among the first players to have been diagnosed, post-mortem, to have suffered from CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

Since his death, his ex-wife, Keana McMahan, has become an outspoken advocate for the advancement of the study of CTE, a passion engendered in her from years of watching the mind of Strzelczyk deteriorate over time and seeing how it affects those around the sufferer as well.

McMahan recently appeared on the podcast of former NFL linebacker Emmanuel Acho, who gave her the platform to speak, and she certainly had a lot to say, beginning with her ex-husband, noting that “Justin was one of the first that was diagnosed. I’m sure you’ve seen the movie Concussion. He was the third player”, she said.

She painted a picture of how it was at the time, in the early 2000s, leading up to his death in 2004. “I was so blown when he was going through this”, she said. “We didn’t know what it was. I thought he had bipolar [disorder]. CTE hadn’t been discovered”. She mentioned that “the coroner took 12 slides of his brain and saved them” after he died, and that it was years later when Dr. Bennet Omalu finally obtained and examined them.

“I couldn’t let it go because I just know how lonely it is”, she said of why she has become so outspoken on the subject. “I was scared, had two small children, my family was three hours away. I have friends that were supportive and helpful, but when you’re in a situation [like that], you can’t go to other players or players’ wives and talk about your husband like that”.

“I was just very alone and I didn’t want more women to go through that”, she went on. But she reminded, “and they will go through that, it’s going to continue to happen as long as there’s football. My story’s not the only one. In the beginning it was one of the only ones, but there’s going to be hundreds more if football continues the way it is”.

“I just couldn’t let it go because I know what it’s like to be up all night crying and trying to find your husband and worried that you’re going to get a call from the police that he died—which I eventually did”, she added.

McMahan has mentioned on several occasions that Strelczyk was never diagnosed with a concussion from 10th grade when he took up the sport all throughout his 10-year playing career, but she said, “I’m sure he had multiple”. He didn’t know what it was, of course. “He also thought he had mental issues”, she noted. ‘He thought it was something mentally”.

She said that she was glad to hear Tom Brady’s wife speak up in public. “This is somebody’s life”, she said. “You get one brain. They can give you a new arm, a new leg, a new lung, a new heart! The brain? No, this is it”.

Players, however, “don’t want to look weak, and they don’t want to lose their job”, noting one game in which he played with a Staph infection and a 104-degree fever. So players are afraid to even talk about concussions, let alone admit that they may have suffered one.

Given the personal experience that she had living with somebody deteriorating from the effects of CTE, McMahan has become bit of a zealot, and she said of the NFL, “I wish it was gone. To me, there shouldn’t be football, period”. She knows that is not realistic, however, but suggested to at least “get rid of Peewee” football.

She said that she is “not over it” after all these years, noting how the league doesn’t do enough for players. “I think they still have a long way to go”, she said. “I don’t think they take care of these men when they leave the field”. She also pointed out that a past concussion lawsuit that produced a settlement for players didn’t even leave Strzelczyk’s family eligible to benefit because it only applied to those who had died since 2006.

McMahan is an active participant in different organizations advocating for more CTE research, and through her work she hears from many people from different walks of life who have had brushes with the brain disease.

“I have a woman that contacted me privately a few weeks ago”, she recounted one such contact. “Her husband played in the NFL. They were on a vacation. He wanted to jump off the balcony. She had to talk him down. He has problems. We’re small women dealing with 300-pound men, and we need help, and you have the money. Do something”, she said of the NFL.

“There are men who are playing on that field today whose wives I speak to who are violent at home”, she went on. “I know kids who have passed away from suicide at age 20 who only played Pop Warner or Peewee and they ended up having Stage-One CTE”.

She recounted the different ways that those she has worked with have tried to cope with living after football and with CTE. She believes that those who have had the most success fending off side effects are those who have remained both physically and mentally active.

Many others have chosen, she said, to lock themselves in a room with a television and marijuana. “They’re suffering and they’re trying to find a way to alleviate the pain”, she said.

McMahan’s eldest child, Justin Jr., did play football, at first. He played up until the high school level, around the time that his father died, before they knew what was wrong with him. When he seemed to lose interest in the game and she confronted him about he, he told her, “it’s what killed Dad”. “Didn’t you notice that three of the four schools I applied to don’t even have a football program?”, he wondered.

As I mentioned earlier, McMahan has become quite a zealot, but I believe that she has become that way because of the opposition that those in her position have faced. She has walked many miles in a set of shoes nobody would ever choose, and few are there to sympathize.

I think it is worth listening to what she has to say about the physical, mental, psychological, emotional, and generally real-world impacts that living with CTE produces on not just the sufferer, but also those who support him or her. It is a zealotry that is needed to balance the discussion.