It was the AFC North clinching play – Antonio Brown’s 63 yard touchdown that vaulted the Pittsburgh Steelers over the Cincinnati Bengals. So you know we’re breaking this one down in the Steelers film room. Let’s dive right in.

DOWN/DISTANCE: 3rd and 8

OFFENSIVE PERSONNEL: Posse (1 RB, 1 TE)

DEFENSIVE PERSONNEL: Nickel

DEFENSIVE COVERAGE: Cover 3

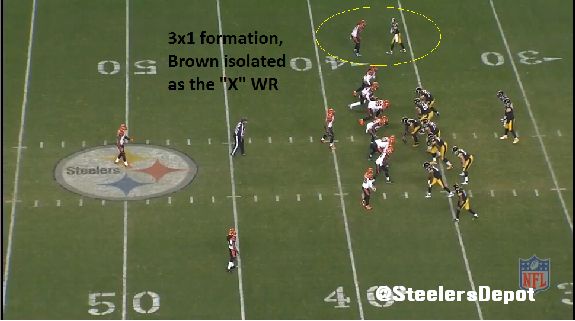

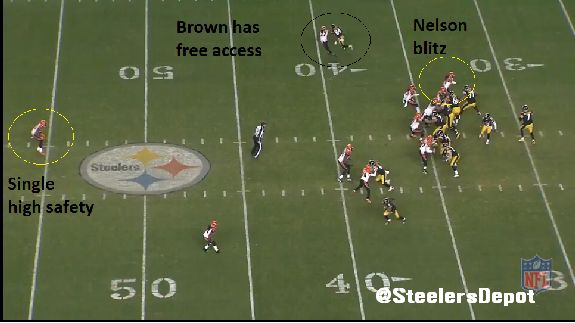

The Steelers come out in a 3×1 look. Brown lines up as the backside “X” receiver. It’s a common theme from this game, from this season. Every team with an elite receiver wants to isolate him. This either forces the defense to declare bracket coverage or leave him on an island pre-snap. Either way it’s is an advantage for the offense.

It’s impossible to know how each team uses this look but it stands to reason – especially given the situation, third down, chance to virtually put the game away – the “X” receiver will be the primary receiver pre-snap. In a recent article I read, that’s what Morrisville State head coach Curt Fitzpatrick looks for.

We’re attempting to determine if the “X” has, as Fitzpatrick coins it, “free access.” Is the isolated receiver truly isolated?

Free access is determined in two aspects.

- The presence of a two high shell with a wide safety

2. An “overhang” player underneath

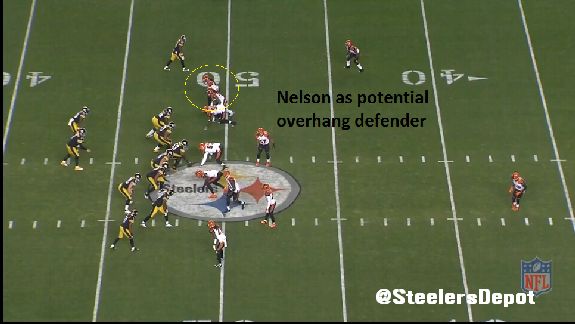

A quick example of an overhang player. First third down of the game for the Steelers.

Ben Roethlisberger must read safety Reggie Nelson to identify him as the potential overhang defender. If he drops, Ben needs to look to the three receiver surface instead.

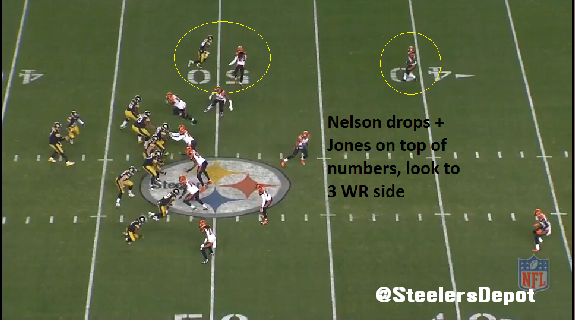

Nelson drops into the hook zone. Plus, cornerback Adam Jones, now acting as a safety, is playing with width, on top of the numbers.

It leaves just a tiny window for Ben to throw and the pass winds up being tipped by Nelson. An example of Ben locking onto his read when he should have went to his second progression.

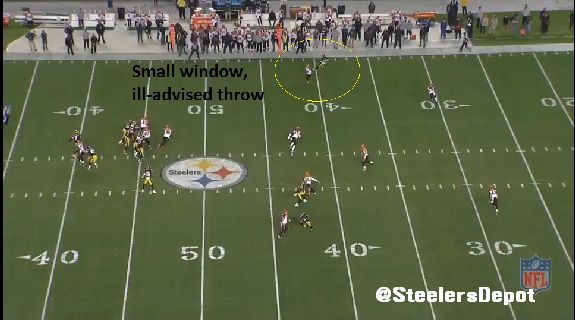

But on the touchdown, there is no overhang. It’s a single high safety, occupied to the middle of the field. Nelson rolls down into the box but doesn’t drop into the hook zone like in the above example. Instead, he blitzes. Antonio Brown has “free access.”

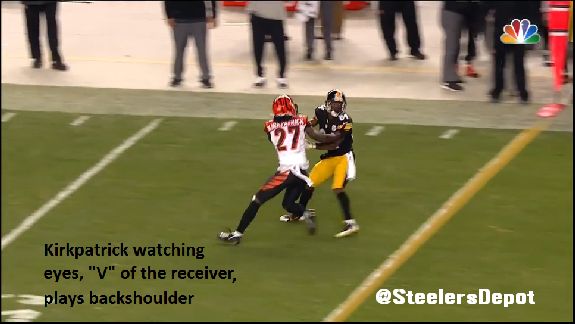

Now onto the route. It looks like a back shoulder fade, similar to something the Steelers ran early in the game.

Of course, here, the throw ends up being in front of Brown, downfield instead of to the outside shoulder. That isn’t a route by design; like many have speculated, this appears to be an improvisation between Brown and Ben.

It takes advantage of the keys a CB has playing this route. When the corner is in phase, he’s taught to read the eyes of the receiver. Or the “V” of the neck of the receiver. The eyes and hands are supposed to take you to the ball.

And that’s what Dre Kirkpatrick rightfully focuses on. It looks like a back shoulder throw. Kirkpatrick, in such a critical down, plays it as such. And aggressively. A breakup gets the Steelers off the field and the Bengals a chance to tie or win the game.

At that point, it’s easy to shake the corner. The deep safety has a flat angle, he’s in a nearly impossible position against a threat like Brown, and is easy to evade. Save for Martavis Bryant getting a little too close for comfort, it’s nothing but green for Brown.

Again, it’s hard to say how this was communicated. Perhaps something kept in the back of both their minds following the missed connection on a true back shoulder throw in the first quarter. Maybe something that has been up their sleeve for weeks.

But what I am certain of is the level of trust shown between quarterback and wide receiver. In the game’s most crucial play, those two have a moment of backyard football. Two tremendous players at their position showing in the heat of the moment, with everything on the line, how good they really are.