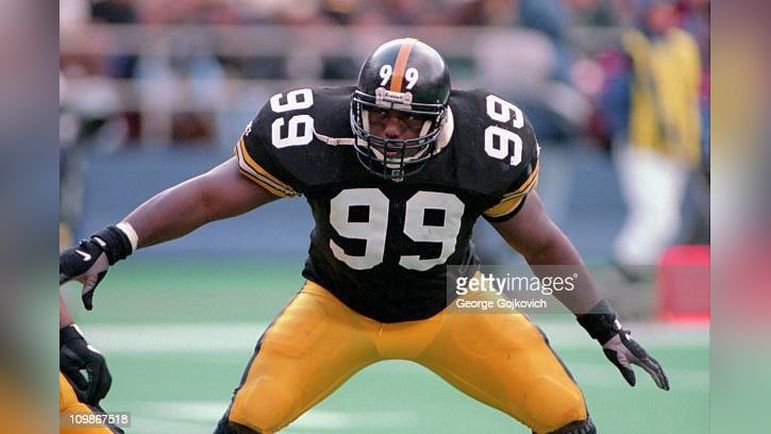

Former Pittsburgh Steelers’ linebacker Levon Kirkland is remembered for one big reason. Literally. Kirkland is one of the largest linebackers in recent NFL history, a clear juxtaposition to today’s game where the league takes a collection of former safeties, makes them 215 pound “linebackers” and calls it a day.

I spoke with Kirkland, a two-time Pro Bowler and one-time All-Pro who spent nine years in Pittsburgh, to reflect on his career. While Kirkland became one of the league’s largest linebackers, he wasn’t always that way.

“When I came into Clemson, I was undersized,” he tells me in a Saturday interview. “I was about 195 pounds.”

And he wasn’t an inside linebacker like he was in Pittsburgh. He played outside linebacker, bulking up to 240 pounds with the Tigers and becoming a college All-American. Eventually, he would be inducted into the team’s Ring of Honor. It wasn’t until the Senior Bowl that he shifted positions, Coach Art Shell moving him to inside linebacker. Kirkland admitted he wasn’t quite sure what he was doing but if he could find the ball, he’d hold his own. He did.

That turned him into the Steelers’ second round pick of the 1992 draft, Bill Cowher’s first haul. Once in the NFL, he continued to bulk up and estimated he played most of his career in the 270-280 pounds range, though he lost some weight in his final seasons. While he was unusually large and broad-shouldered for the position, Kirkland was also a fantastic athlete and his size never hindered him. He intercepted eleven passes in nine seasons with Pittsburgh, making countless other plays in coverage.

“I didn’t really get heavy intentionally. What happened was I was still so good at that weight, especially around 270, 280, I was probably no different than any linebacker that was weighing 230. I could run, I can cover tight ends down the field. So it wasn’t that much of a difference comparatively speaking to other linebackers.”

He was the self-described “enforcer” of the Steelers’ excellent linebacking group, playing alongside names like Kevin Greene, Greg Lloyd, Earl Holmes, and Jerry Olsavsky. Kirkland’s size was an asset for the era, the game played largely inside the box with big linemen and lead fullback blockers to battle with.

Despite being a high draft pick, he wasn’t an immediate impact player. A backup his rookie year, he quickly understood the NFL didn’t follow the college model.

“I was naïve when I first got in. I thought that, like in college, you did a lot of rotation. In college, we rotated a lot. So I thought it was the same in the NFL that you’re gonna rotate. If you wouldn’t be a starter, you’d get some playing time. I quickly realized, if you’re not a starter, you’re not getting any playing time.”

Kirkland became the starter in his second year. And he shined. He finished second on the team in tackles in 1993 and 1994, recording over triple-digits. A versatile and well-rounded player, he could stuff the run, sack the quarterback, and pick them off in the pass game. In 1996, he earned his first Pro Bowl berth and in 1997, he made his first All-Pro. In the latter year, he finished with 126 tackles, five sacks, and two picks. He’s the only Steeler with such a single-season stat line, 120+ tackles, 5+ sacks, and 2+ picks. And Pittsburgh’s tradition at linebacker is as strong as anyone in franchise history. Kirkland was also remarkably durable, one of the most durable Steelers’ ever, never missing a game in his nine-year Pittsburgh career.

But all good things come to an end. Kirkland’s time in Pittsburgh was an abrupt and unceremonious finish. He didn’t find out he was going to be released after the 2000 season by the team or his agent. Instead, the news was broken to him by a reporter.

“I got a phone call from Ed Bouchette that told me that they were thinking about getting rid of me or thinking about waving me.”

In a cost-cutting measure, Kirkland was one of several Steelers’ veterans released that year. It was difficult news to digest after nine years with the team, believing he’d end his career there. It was doubly tough knowing how close the team was to making another run.

“I knew that the next year we’re gonna be really good. And I even told the team, ‘let’s get prepared cause next year we’re gonna make a run.'”

Kirkland was right. Pittsburgh got back on track in 2001, advancing to the AFC Title Game before falling to the New England Patriots. Kirkland found a home out west, signing and starting all 16 games with Seattle. He moved onto Philadelphia in 2002, again playing in all 16 games before his career came to a close.

These days, Kirkland still follows the Steelers and considers himself a fan, though not a die-hard. He’s still close with Clemson football, hosting a podcast covering the Tigers.

Though he played in an era where football looked and was covered far differently, without the 24/7 scrutiny, fantasy football wasn’t nearly as popular, and sports betting only existed in dark corners of casinos, Kirkland understands and accepts the evolution of the game. But he warns NFL defenses not to sacrifice size and run defense at inside linebacker just to play someone who can cover.

“Trust me, if you can’t play the run, I don’t care what era it is. It is tough. If you can’t stop the run, it is physically demoralizing. I don’t think you could just simply put a guy that was a safety and say, ‘hey, why don’t you play linebacker?’ I think it’s gotta be a guy that has the combination of both. Who can really play the run but also be able to be effective in the passing game.”

Overshadowed by legends like Jack Lambert and Jack Ham, Kirkland was one of the NFL’s top linebackers of the 90s. Though he couldn’t end his career with the team he started with, he loved playing in and for Pittsburgh.

“I just love playing in Pittsburgh because the fans really understood the game. They were knowledgeable fans, they were behind us. It was a culture. It was something that from the 70s on, people grew up being a Pittsburgh Steelers’ fan. They probably had a onesie that had Steelers on it or a football or a Terrible Towel. They really took the game seriously and they bought into the culture because the culture was Pittsburgh as well.”