This Sunday’s divisional matchup between the Pittsburgh Steelers and the Baltimore Ravens is shaping up to be a classic. Already bitter rivals, the two teams match up with strength against strength. The Steelers are arguably the stoutest running-stopping defense in the NFL. Allowing only 3.4 yards per attempt, they are second in the league only to Tampa Bay. Over the course of six games, the Steelers have only let teams rush for a total of 413 yards, which is best in the NFL at just 68.8 yards per game. The Ravens come into the game leading the league in rushing with 164.3 yards a game.

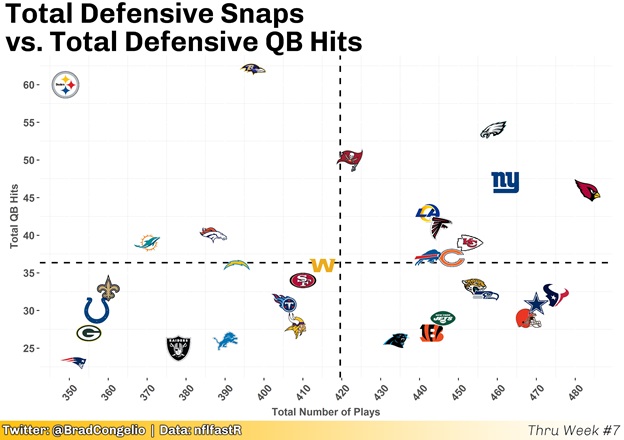

Often, when two immovable forces collide like this, it is other prevailing scenarios that ultimately win the contest. In this case, I argue that the most important secondary storyline on Sunday is going to be which quarterback is able to best handle the onslaught of pressure from the opposing defense. The below graph highlights this quite well, as the Steelers and the Ravens are far above the rest of the league in total defensive QB hits, with many less total plays run. Both teams are able to get to the opposing quarterback at an incredibly efficient and, frankly, frightening rate.

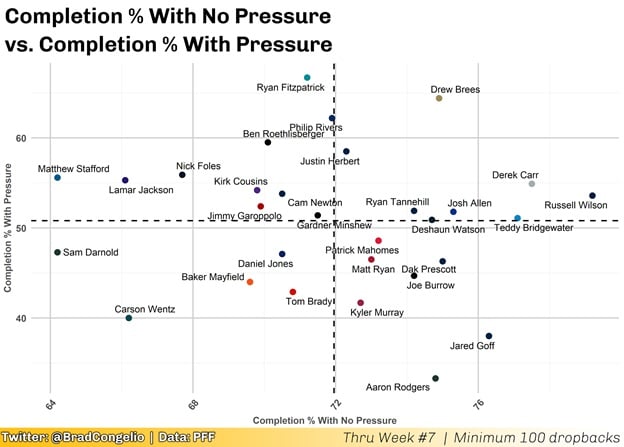

If the wildcard of the game truly becomes which quarterback – Ben Roethlisberger or Lamar Jackson – handles the pressure better, who is likely to come out on top of that battle? To examine this, we can start with a look at the completion percentage of each when facing pressure and when not facing pressure. It is important to note that the Ravens do have, statistically, one of the worst passing attacks in the league with just 177.8 yards per game. But that is somewhat misleading, as there is less need to pass when an offense is as strong on the ground as the Ravens are. That said, surprisingly, both Roethlisberger and Jackson are among the best quarterbacks in the league at still finding open receivers despite facing pressure. There is no clear winner using this metric, especially since Jackson has the ability to scramble when under pressure and Big Ben is often difficult to take down.

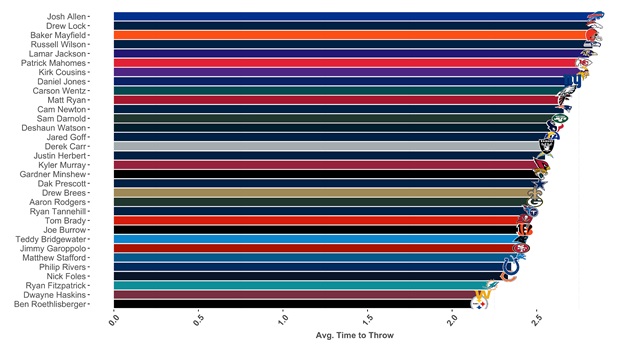

Because of that, we can also view this battle of quarterbacks handling pressure through the lens of average time to throw. And this is where Roethlisberger starts to pull away and gives me hope that the Steelers can earn a victory when the running offense vs. running defense stalemate shifts the balance of the game into the hands of each quarterback. Because of the amount of pressure each defense is likely to bring, Roethlisberger’s ability to quickly get the ball out of his hands is going to be paramount. In fact, Roethlisberger is currently the fastest-to-release quarterback in the NFL, getting rid of the ball, on average, in just over two seconds. Jackson, on the other hand, is holding on to the ball until almost the three-second mark after the snap.

Indeed, some of Roethlisberger’s most valuable plays according to the expected points added (EPA) model have occurred when he gets rid of the ball between 2 to 2.3-seconds after the snap. As well, it seems that he is operating best in these circumstances in both the shotgun and no-huddle offenses.

Case in point, facing a third-and-7 on the Giants 10-yard line, Roethlisberger zipped a short pass to the left in 2.1 seconds, finding JuJu Smith-Schuster wide open for a touchdown. The play ending in a score obviously increases the EPA – which was 3.15 – especially since it occurred in a third-down situation.

The examples of Big Ben being most productive with quick throws is well-documented thus far this season. Against the Giants, Roethlisberger found Smith-Schuster on a short pass over the middle for an overall EPA of 0.97. The 14-yard gain on the play moved the chains on the second-and-10 attempt. On this play, Roethlisberger held the ball for 1.9 seconds, quick enough to stymie any push rush being brought by the Giants.

Against the Broncos, the Steelers faced a first-and-10 midway through the 3rd quarter. Roethlisberger found Diontae Johnson on an out route just before midfield. With an overall EPA of 0.67, the ball was out of the pocket in a speedy 1.7 seconds.

As one last example, Roethlisberger found Anthony McFarland sneaking out of the backfield for a 7-yard gain on a second-and-8 against the Texans. While the EPA was only 0.57, as the play didn’t result in a new set of downs, Roethlisberger’s ability to play well when he is playing fast is again well sampled after getting the ball out of the pocket in 2.03 seconds.

It is fair to argue, I believe, that Roethlisberger will need to continue playing a speedy version of football against the Ravens pass rush. This ultimately plays to his strength, however, as highlighted by his high-level EPAs in such situations, as sampled in the above videos. But, in order to fully justify that, we need to know how quickly the Ravens defense has been getting to quarterbacks.

Unfortunately, there is no easy way to quickly access that information. Which means it is a good thing that I do not mind doing a little dirty work to figure out the numbers. By using the advanced stats from Pro Football Focus, one is able to collect the average time in the pocket for each quarterback on a week-by-week basis. By doing so for each quarterback to face the Ravens thus far, we are able to establish a general baseline on how quickly the Ravens imposing pass rush is able to force the quarterback out of the pocket, which I argue is a good measurement of “play disruption.”

According to the data, the Ravens defense has caused enough of this disruption to force the opposing quarterbacks, on average, to move out of the pocket approximately a tenth-of-a-second sooner than the season average. In a game that is often measured by tenths-of-a-second, that is something that should not be ignored.

Unfortunately, it is a different story entirely for Jackson. It takes the agile quarterback over 2.8 seconds, on average, to get the ball out of his hands. The Steelers pass rush, on average, has forced quarterbacks out of the pocket in about the same time. So, while Roethlisberger – based on the averages – should be OK, Jackson may very well be running for safety on many passing downs (which brings up another set of challenges for the Pittsburgh defense, as Jackson isn’t just any other old quarterback when he escapes the pocket).

The final point is this: football is ultimately a game of seconds. Even tenths of a second. In this case, those tenths of a second could be the difference between Roethlisberger quickly getting the ball out of his hands similar to how he has during high-EPA plays throughout the season. They could also be the difference in watching Jackson struggle to compensate for his tendency to hold on to the ball longer than Roethlisberger while facing a front seven statistically proven to be able to get to him within that timeframe. The wildcard here, as far as I am concerned, is Pittsburgh’s ability to contain Jackson on the edges once the pass rush forces him out of the pocket in that 2.5 to the 3.0-second timeframe after the ball is snapped. If the Pittsburgh rush defense is able to muddle the Raven’s ground game, the statistics seem to indicate that the Steelers maintain the advantage in the passing game vs. pass rush battle between the two teams.