During the first defensive drive in their game against the Los Angeles Chargers on Sunday Night Football, the Pittsburgh Steelers were dealt a huge blow when Stephon Tuitt left with a reported pectoral injury. He returned to the sideline in a t shirt without any wrap or brace but was noted by spectators to be keeping his right arm close to his side. Steelers fans held their collective breath for a day and got the bad news on Monday in a tweet from Chris Mortenson:

It was a huge blow for the team and also for Tuitt, who was arguably having his best season ever. He will undergo surgery and miss the rest of the 2019 season. Sadly, no need for me to speculate on when he might return. But the good news is that with surgery and rehab, Tuitt should have a complete recovery and be ready to roll in time for training camp next year. If you want to understand a bit more about pectoral injuries, read on.

As always, we’ll start with the anatomy. The pectoralis major muscle, more commonly known as the “pec,” is a large muscle located on the anterior chest wall. This broad muscle originates at the clavicle (collarbone), the sternum (breastbone), the ribs, and an extension of the upper part of the external oblique abdominal muscle. The muscle fibers extend across the chest and attach to the upper humerus via the pectoralis tendon. It plays an important role in shoulder function by providing internal rotation (rotating the joint toward the body) and adduction (bringing the arm towards the body). The pectoralis minor is a much smaller muscle which lays behind the pec major, arising from the ribs and inserting into the scapula (shoulder blade) and helps to pull the shoulder forward and downward.

The pectoralis major may tear or rupture in various parts of the muscle. While it’s not a common injury, most pectoral injuries involve a rupture of the tendon off the humerus bone. A majority of pectoral injuries occur in muscular males between the ages of 20 and 50 and the most frequent mechanism of injury is bench press. As explained in “Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation: a Team Approach”: there appears to be a correlation between the mechanism of injury and site of rupture. Tears of the muscle belly are more common with direct trauma; however, indirect trauma leads to avulsion of the humeral insertion or injury to the musculotendinous junction. A pectoralis rupture is commonly accompanied by an audible “snap” or “pop”.

Other less common tears can occur, such as within the muscle belly itself or at the junction of the muscle and tendon (musculotendinous junction). The muscle can also tear off the sternum, which is really rare.

In other sports, such as football, the tendon can tear when there is extreme force on the arm while it is in an abducted, extended, and externally rotated position or with severe traction on the arm. This was the case with Tuitt, as you can see here:

As Tuitt comes around from behind Philip Rivers, his right arm is pulled up, out and away from his chest.

In the NFL, pectoralis muscle injuries are not that common. In a review of the NFL databank from 2000 to 2010 published in The Physician and Sports Medicine, only 10 injuries were found, 5 in defensive players while making tackles. 8 ruptures were treated operatively, and 2 cases did not report the method of definitive treatment. The average days lost was 111 days (range, 42-189). The incidence was 0.004 pectoralis major ruptures during the 11-year study period.

With a rupture of the pectoralis muscle, it’s typical to experience a sharp tearing sensation and there will be resistance when trying to rotate the arm forward. The shoulder may also be painful and weak.

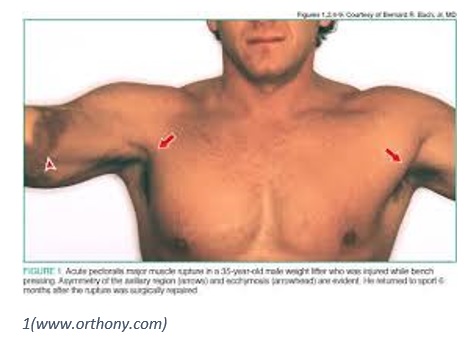

The diagnosis can usually be made just based on clinical exam. There can be extensive bruising and the pectoralis muscle retracts medially, leaving an indentation near the shoulder:

An MRI is used to confirm the diagnosis and assess the extent of the muscle damage. In Tuitt’s case, the MRI confirmed that it was a complete tear of the tendon rather than a partial tear.

A partial rupture or an injury that basically involves tears in the muscle may not require surgical treatment. Instead, the RICE approach may be used: rest, ice, a sling to immobilize the injury, and NSAIDs for pain relief.

If the tendon has been torn away from the bone, surgical treatment is recommended, especially when it involves high-level athletes. Surgery yields excellent results as far as return to pre-injury strength. A study in the British Journal of Sports Medicine compared the results of operative and conservative management and found that “in patients who had surgical repair, peak torque returned to 99% of that of the uninjured side and work performed returned to 97%. For those managed conservatively, peak torque and work performed returned to only 56% of that of the uninjured side”.

You can see a pectoralis tendon repair here, as performed by Dr. Peter Millett at the Steadman Clinic in Colorado (you’ll have to sign in to google, since it’s considered “graphic”). For a detailed rehabilitation plan, check out this paper from the North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. The typical recovery time is 6 months.

In recent years, several NFL players have undergone surgery for a pectoral injury and come back to play at the same level. Redskins CB Fabian Moreau suffered this injury on his pro day in 2017, underwent surgery in March 2017 and was able to play in September, a very fast recovery. Patriots LB Dont’a Hightower had his pectoral injury repaired after an injury in October 2017 and was ready for the following season opener. For Steelers fans, the most notable is Cam Heyward, who sustained this injury in November 2016 and came back better than ever the following year. I expect we will see the same with Tuitt, who should be ready to rock when training camp opens in 2020.