My favorite movie, and move series, is Die Hard. The original, released in 1988, still easily the best. In fact, there’s a clear order of how you should rank each movie of the franchise.

1. Die Hard

2. Die Hard with a Vengeance

3. Live Free or Die Hard

4. Die Hard 2

5. Power outage

6. A Good Day to Die Hard

The latest one made aside, every rendition is awesome. Movie buff or not, everyone is at least familiar about John McClain saving the world.

But Die Hard didn’t just become Die Hard. It wasn’t an original concept. Like so many other movies, there was a precursor to the franchise, a fact lost to history. The movie is based on the the 1979 book, Nothing Lasts Forever, by Roderick Thorpe. Same premise, similar characters (the book had Al Powell and Stephanie Gennaro, instead of Holly), you get the idea. In fact, even that book is based on a prior one from Thorpe, The Detective, made into a movie in 1968 and starring Frank Sinatra.

Circling back to Die Hard, Bruce Willis was far down on the list of choices to star as McClain. Contractually, Sinatra had to be the first one offered but he turned the idea down. So did many other A-list names: Arnold Schwarzenegger, Burt Reynolds, Sylvester Stallone, and several others all said no to the movie. The studio settled on Willis, more known for his commercials and rom-coms than being an action hero, but the movie was a smashing success and the rest is history.

It’s all thanks to what came before the movie: Thorpe’s book.

When I think of how Die Hard was born, I think of the Pittsburgh Steelers. There’s a common thread There is the best part, the massive success. That started in the 1970s with Chuck Noll and the dynasty he created. Since then, the Steelers’ franchise has been iconic, a beacon of success and stability, and thankfully, don’t have any Die Hard 5 type clunkers.

But just like Thorpe’s book and Die Hard, the Steelers’ franchise wasn’t born with the arrival of Noll. It has a long history before that point, from 1933 to 1968, lost in history. Since this is the offseason, I want to continue to highlight the pre-Noll era because it’s forgotten about. The team was bad, time passes by so it’s easy to discount. However, the Steelers’ history then was rich, even if it didn’t translate to the team’s success.

So think of this series as Nothing Lasts Forever. Our ode to those who didn’t get to enjoy being on top of the world. But they’re the players who helped shape the franchise.

We’ll start this series with Angelo Brovelli, who played with the team from 1933 to 1934.

Angelo Brovelli

The stars on the Steelers’ today are easy to name: Ben Roethlisberger, Antonio Brown, Le’Veon Bell. Ask any Steelers’ fan about Joe Greene, Jack Lambert, or Lynn Swann, and you can strike up a conversation over a couple – or many – beers. But arguably the team’s first “star” was Brovelli, part of the original team founded by The Chief in 1933.

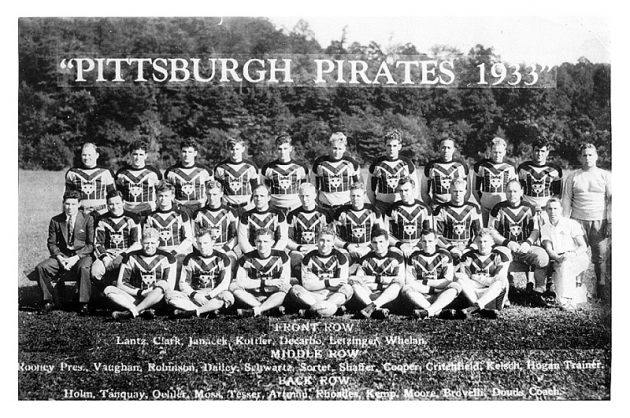

Pittsburgh, as you may know, weren’t born as the Steelers. They were originally called the Pittsburgh Pirates, a common tactic back in the day to feed off baseball’s popularity. For our purposes though, we’ll refer to this era as the Steelers to tamp down the confusion.

So it was Brovelli who signed with the team, coming all the way over from St. Mary’s, the Gaels, in Moraga, California. It was Brovelli who graced the Pittsburgh Press’ first preview of the team before their inaugural game in September of 1933. They would take on Harry Newman and the New York Giants.

At the time, the excitement was justified. Brovelli had a strong college career for the Gaels. He played a key role in one of the biggest upsets of the 1930s when St. Mary’s traveled across the nation to knock off powerhouse Fordham 20-12.

The school was appropriately enough coached by a star of their own, Slip Madigan, a former Knute Rockne assistant who lived a life of luxury. 150 fans were invited by Madigan to travel to the game, for example, in a 16 car train that, as the San Francisco Gate put it, offered “the world’s longest bar,” though I’m not quite sure how that meshed with Prohibition laws of the time.

Despite Madigan wining and dining the East Coast and inviting countless celebrities to a party the night before the game, St. Mary’s were heavy underdogs to Fordham. The first half proved just that with the Rams taking a 12-0 lead.

As the story goes, Madigan laid into his team at half, wrapping up his speech with the following line.

“The human heart is made to win. Do you hear me? The fighting human heart is made to win. Now, who will win for old St. Mary’s?”

Brovelli reportedly piped up and responded, “I will, Slip!”

That turned the tide for the second half. While he didn’t score, and left the game early after several strong dives into the Fordham defense, Brovelli ripped off several long runs. They scored three times in the second half, Fordham was shutdown and shutout, and the upset was cemented. The team would celebrate with a trip to Washington D.C. to meet President Herbert Hoover.

In attendance that day was Fordham alumni Wellington Mara, the original owner of the Giants, who credited Brovelli as the catalyst.

“Angelo Brovelli ran over Fordham in the second half,” Mara said, via a New York Times article from 1995.

Here’s one photo of him in college, the lead back of the successful Gaels’ squad. He’s the centerfold on the left page.

The NFL draft wouldn’t exist for another three years from Brovelli’s rookie year with the Steelers in 1933. I’ve never been able to find out exactly what compelled him to join the startup Steelers. Perhaps that can be contributed to Art Rooney selling him on the franchise.

Listed as the team’s starting left halfback for the 1933 season, Brovelli was thought to be a key cog in their double wing offense. The high praise the papers gave to him before the season faded as quickly as it appeared. The Giants drubbed Pittsburgh 27-2 in their first game. He was called a “disappointment” by the Post Gazette and responsible for the first turnover – and points – the Steelers ever gave up. Ken Long picked off his pass intended for Paul Moss, another great story by the way, and housed it from 34 yards out for the first score of the game.

Things did get better the following week, catching a 59 yard pass from Tony Holm in the franchise’s first ever victory, a come-from-behind 14-13 win over the Chicago Cardinals.

He had the only score for the team one week later in an otherwise uneventful 21-6 loss to Boston and moved to quarterback the following week in a roster shakeup. Pittsburgh notched another win over the Cincinnati Reds, 17-3, with Brovelli ripping off runs of 19 and 16 yards.

Per Pro Football Reference, he finished the 1933 season with 60 carries for 236 yards and a pair of rushing scores while chipping in another six receptions. He completed eight passes to his team, three to the other guys. Brovelli is considered the team’s first quarterback, though due to the era and offense the team ran, it was mostly in name only.

Much like Noll, though obviously, this was the 30s so roster turnover was common and loyalty wasn’t even a thought, coach Luby DiMeolo overhauled the 1934 roster. Brovelli was one of only three players from the ’33 squad who remained; plus Jap Douds, who removed the “coach” part from his “player-coach” moniker.

It was a much tougher season, Brovelli now just another face, and the papers rarely said he did anything notable. There was one touchdown, scoring on 4th and goal from the five in a 9-7 victory against the Philadelphia Eagles. Two weeks later, he fractured his left shoulder in the first half against the Bears – a positively dreadful game for anyone donning those ugly Steelers’ uniforms – and by the next week, Brovelli was traded to Boston. More accurately, left in Boston, as the team traveled up there to play that week. And lose. Again.

If there’s a record of Brovelli playing pro football after that, I’ve been unable to come up with it. PFR makes no mention of even his time in Boston. But pro football wasn’t covered the way it is now. Not even close. Baseball was firmly entrenched as the game’s pastime and college football had tenure, making it the game to watch over the NFL. Unless Red Grange was around, no one cared about the pro game.

In Lew Freedman’s book on the history of the Steelers, Brovelli is quoted as saying: “We played in Forbes Field and we didn’t draw flies.”

Perhaps it was facing the likes of Bronko Nagurski that made Brovelli decide to bow out of the sport. A great quote from him, as collected by the LA Times.

“I tried to stop Bronko Nagurski,” he said. “Ever hear of him? He educated me. When I tackled him, it felt like my shoulder was sitting on my hip.”

I imagine many defenders will one day reflect the same about Jerome Bettis.

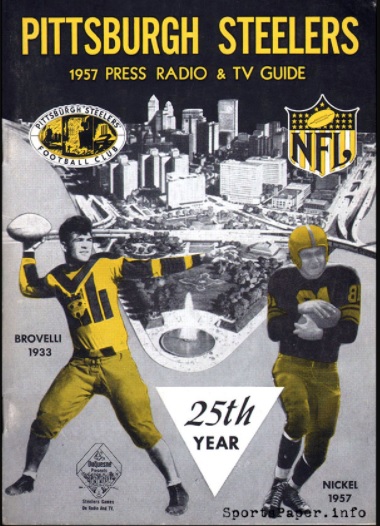

Brovelli’s name was not entirely expunged from Steelers’ history following his 13 career games with the franchise. He was featured on the cover of this 1957 Steelers’ media guide, the franchise celebrating its 25th year, alongside Elbie Nickel. From past to then-present.

Post-football, Brovelli and his wife moved back to California and the city of Lodi. He dedicated the rest of his life coaching sports and starting a Boys & Girls club to stress the game’s importance not only for the values it teaches but its ability to provide an education, just as it did for himself.

“He would tell them, ‘If you put as much into education as breakdancing, you would be an A student,'” his daughter, Barbara, told the Lodi News-Sentinel in 2012. Her and her father were inducted into the Lodi Community Hall of Fame that year for all they did for the community.

He passed away in 1995, buried in his home state of California and next to his wife, who died ten years before.

In the NFL, it’s tough to argue Brovelli had a particularly successful career. Definitely not a long one. But he was the first “name” player to ever come through the Steelers’ franchise and someone who enjoyed a strong football career in general.

His impact in the community and trickle-down effect is something that, unlike any football career, will last forever.