I am not a doctor.

We use that phrase as something that’s usually tongue-in-cheek. Or a preface before making the best guess at a player’s injury as we can. Most of the time, unless you spent the 29 years in medical school, our words are hollow.

But there is one thing I know. One thing we should all know. Concussions are football’s most serious threat. And not enough people realize that.

Pete Rose’s comments last week reminded us of how so many people don’t understand their danger. Sure, it was baseball, but the ignorance all the same.

Here is what he said after the Toronto Blue Jays’ Josh Donaldson left a game after colliding into second base, according to SB Nation.

“Does everybody know what we’re playing for now? I mean, you get a tweak and you got to leave the game. You take a knee to the head, and you’ve got a helmet on, and you gotta leave the game to go take a test that you pass. I mean, because you’re a little light-headed?

I got light-headed how many times in my career? I still went out there and played. I guess it’s just different from when I played to when they’re playing today, Frank. I can’t see you sliding into second there and leaving the game, I really can’t.”

Sure, Rose lived in an era where if you were conscious, you played. But it’s a shame to see someone whose opinion hasn’t become malleable despite the overwhelming new evidence of the life-altering and life-ending results concussions leave too many players with.

We were reminded again of that devastating result with former Pittsburgh Steelers’ outside linebacker Adrian Robinson’s autopsy results, revealing the 25 year old to be suffering from CTE, a degenerative brain condition, that resulted in him committing suicide. Robinson left behind friends, family, and most importantly, a one-year old daughter. According to the family’s lawyer, those who knew him well said he went from a kind, caring person to having a “darker edge.”

Too many ex-Steelers have dealt with the same, though often after their careers are done. Lineman have it particularly tough, years of small hits accumulating over time. Maybe the most famous case is Mike Webster, the Hall of Fame center.

Iron Mike. Until the disease took that shine away from him.

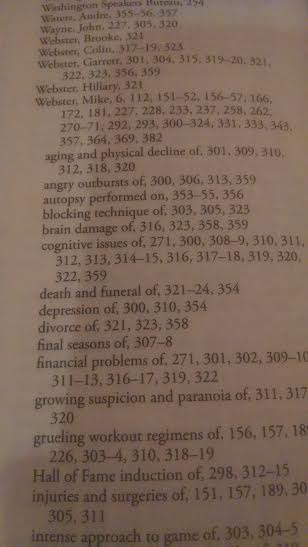

I’ve always known Webster dealt with demons he finally succumbed to. But I didn’t realize just how terrible it was until I read Gary Pomerantz’s book, Their Life’s Work. Before even reading it, look at the index and all the sub-listings under Webster.

Phrases like “angry outbursts,” brain damage,” “death and funeral,” growing suspicion and paranoia of,” appear. Not “nine-time Pro Bowler”, “217 game starter”, “best of his era.” Reading about his life in Pomerantz’s book creates a darker image. I’ll include a couple passages.

“That Webby was losing touch with reality soon became clear to [Kansas City Chiefs’ President Carl Peterson] from letters Webster sent him. They were longer and more rambling than before, written in longhand with a pencil. Passionate, yes, but they were beyond repetitive….his earnings dried up. He made less than $6000 in wages in 1991, and no wages at all in 1992 and 1993. “

“He was in his early forties but looked at least a decade older. He suffered intense physical pain from sharp headaches, arthritic joints, a torn rotator cuff in his shoulder, from nerves activated and desiccated and ruptured spinal discs, from hands and fingers mangled and swollen from being bend and stepped on at the line of scrimmage, and a right heel that felt almost as if a spear were stuck in it…he ate poorly, if at all. From lack of care, his teeth rotted. He took a long list of prescribed medicines – Darvocet, Vicodin, Prozac, Ritalin, Dexedrine, Klonopin, Ultram, Paxil, and Lorect – to combat pain, inflammation, attention deficit, anxiety, and depression.”

“[Craig Wolfley, Ted Peterson, and Tunch Ilkin] searched for an apartment for Webster near their own homes, so together they might keep watch over him. But first they bought a plane ticket for him to return to [wife] Pam and the kids for Christmas; he stayed in Wisconsin for some time. When he returned, Webster grew increasingly suspicious of his former teammates’ help. ‘He got really suspicious of me, and I couldn’t believe it,'” Ilkin said. “‘And that hurt.'”

“Soon Webster was sleeping in his pickup truck outside [caretaker] Jani’s grocery store, and on the couch in the back office…Webster called Jani in the middle of the night to say he was in his truck, pulled to the roadside confused, and unsure of where he was. Jani drove nine hours, nearly to Milwaukee, to get him. Jani began to duct-tape money in hidden places in Webster’s truck in case he got lost again.”

“Two doctors treating Webster told reporters that Webster’s frontal lobe had been damaged by too many hard hits on the football field and that he suffered a condition similar to dementia. It affected his moods, and decision making. He needed Ritalin, one doctor said, and asserted that Webster’s brain injury could not be healed. ‘All you can do is control the symptoms.'”

That alone is heavy information and sadly, only a few paragraphs of several pages Pomerantz wrote detailing Webster’s final years. They are hard to write and I’m sure harder to read, especially if you’re seeing it for the first time. But that harshness is exactly the point. There is no benefit to sugarcoating what happened. We must continue to face, embrace this evil side. Continue to educate current players on these very real dangers.

No, concussions can’t be eliminated entirely but the message has to be clear: there is no pride in “sucking it up” and playing through a concussion. There is only regret.

Adrian Robinson wasn’t a well-known name. And that makes his story, his life, easy for us to forget. But he was a person. He was 25. Gone too soon in an all too familiar story.