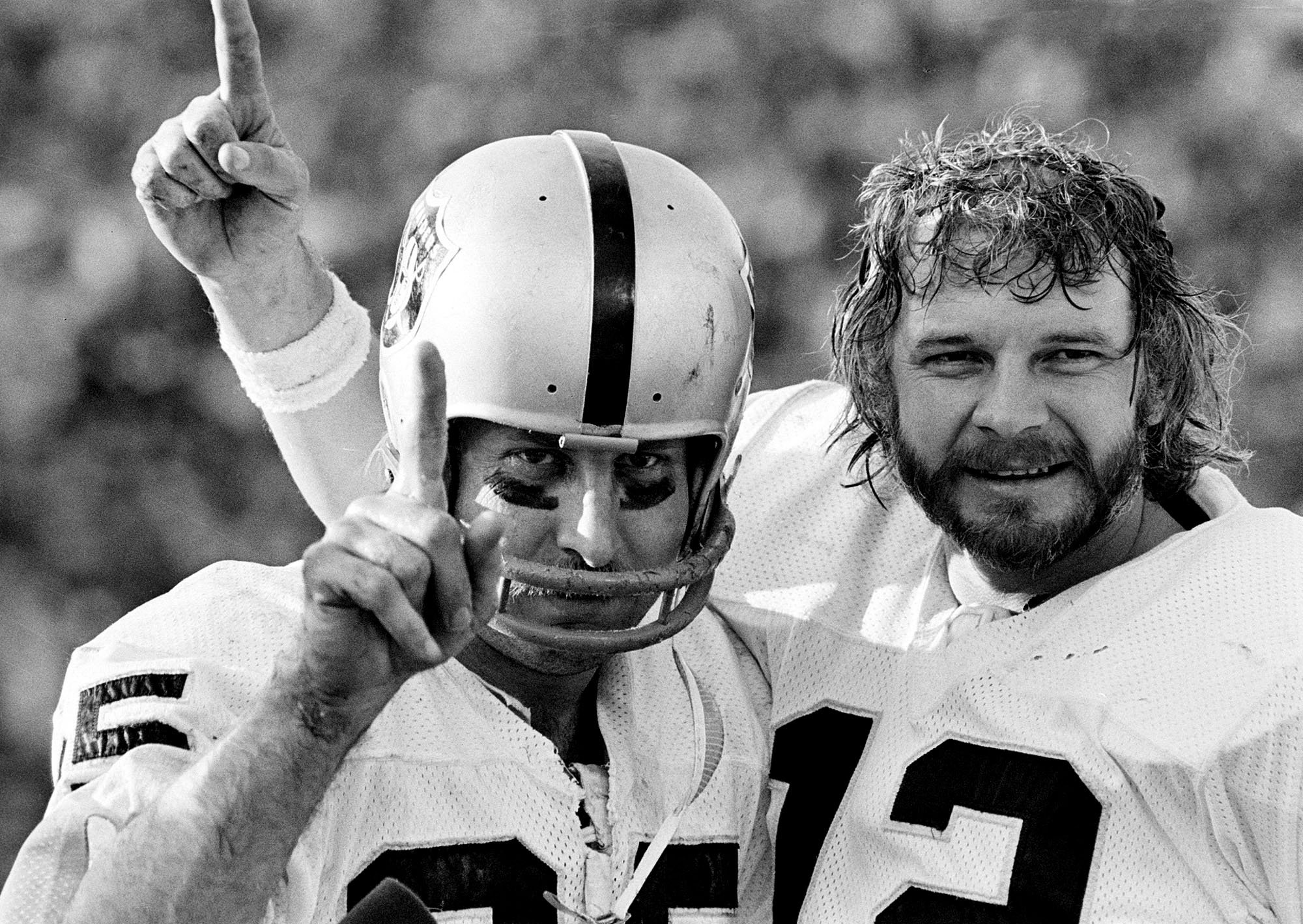

This past Thursday brought us the sad news of the passing of former Oakland Raiders quarterback Ken Stabler at the age of 69. A highly accomplished football player in his own right, and one of the key figures in one of the greatest rivalries in NFL history between the Raiders and the Pittsburgh Steelers of the 70s, his legacy for his on-field exploits is more than well-cemented.

And while his ‘rebel’ persona off the field will also be a part of his legacy, perhaps one day one of his greatest contributions will be remembered as his decision to donate his brain and spinal cord to science upon his passing in order to be studied for degenerative brain disease as a result of chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

About three years ago, Stabler joined on to what was then already a massive 73-player lawsuit filed against the NFL pertaining to its negligence in dealing with concussions sustained while playing the game.

An interesting aside to that is the fact that Steelers outside linebacker James Harrison was named in that lawsuit as one of the league’s “recidivist violators”, whose aggressive play in 2010 helped force the league to tweak its rules, or at least the enforcement of the rules, mid-season.

When asked about the lawsuit and about Ken Stabler joining on, Harrison asked, “Ken who?” After being informed, the former All-Pro said that he has “never heard of him” and that “his opinion doesn’t matter to me”.

But it’s obviously a topic that mattered a great deal to Stabler, who played the length of his career during an era in which concussions were referred to through euphemisms such as ‘getting your bell rung’ or ‘seeing stars’, with the expectation that you’ll get back in the game.

There is little question that the league made efforts to suppress their knowledge of the severity of the harm that traumatic head injuries might have later in life for a period of time, during which a great deal of professional athletes played their careers without suitable protections that have since been implemented—much to the chagrin of traditionalists of the sport.

While a great many strides have been made in the intervening years with the study of brain injuries, as well as the league’s compliance with and perhaps begrudging adaptations of necessary precautions and safety nets, it’s clear that there is still work to be done.

One difficulty during this journey has been obtaining appropriate samples to study, which is why it’s so valuable when an athlete agrees to donate his brain to science for evaluation, which has the potential to do a great deal of good for future generations of not just athletes, but anybody who suffers from generative brain disease.