Over 110 million people sat, glued to their television for Super Bowl 49. Another 70,000 plus saw it in person. It’s a sport with a salary cap eclipsing the $143 million mark, a figure we throw out without even realizing its enormity. Even today, in the dead of the offseason, fans find themselves enthralled with every scrap of news they can get their hands on. It’s the NFL craze and like it or not, it’s not going to stop.

To beg the question, how did it start? How did we get here? What is football’s version of The Big Bang? The initial explosion that created today’s landscape

Search “first football game” on Google and the first entries that appear all reference the same game.

That’s Wikipedia listing the 1869 game between Princeton and Rutgers as the first. It has to be true.

Though this is meaningless to some, after all, it did take place over 130 years ago, that “fact” is far from the truth. Football didn’t resemble the sport we know and – for the most part – love, for over another decade.

Though there are numerous arguments, yet the best and simplest one I can give involved another quick search. Look up “father of football,” and it yields this result.

Here’s the confliction in the argument. You can’t propose the first football game took place in 1869 and claim Camp is football’s father. In 1869, he was ten years old. The child of football perhaps. Not the father.

If you accept Camp being the pioneer to create the foundation of today’s game, which you should because it is undoubtedly the truth, the more accurate timeline puts modern day football to 1882.

In 1869, football didn’t exist. An archaic form of rugby was played in the 1850s, a glorified scrum to give college kids an excuse to beat up on each other. Concerned over the violence of the game Harvard banned it in 1860.

The score itself from the “first” game shows it. While even Camp’s scoring system differed from today, the ’69 game ended in a 6-4 score. Immediately, that should raise some eyebrows if this was really football. The fact each side played with 25 men should obliterate the fact this even remotely resembled American football. It was soccer.

The game was supposed to be a three game series and after Rutgers’ initial victory, Princeton evened the series with an 8-0 win one week later. The third game was never scheduled after neither side could agree on the rules. That was common for the time, each side attempting to convince the other. Usually, the home team got their way.

Courtesy of Pro Football Researchers, they got ahold of the 12 rules established four years later in 1873.

It’s a delight to look at. Interesting to see how the game evolved. But football? No way. At this point, it’s not even football. It’s still soccer.

Luckily, FIFA didn’t get involved.

What if I told you we should thank Canada for football?

Immediately, it sounds like the premise to a 30 for 30 documentary. But largely, it holds a lot of truth.

McGill University in Montreal served as the catalyst. In May of 1874, they challenged Harvard to a two day competition. On the first day, they’d play under Harvard’s soccer rules, a game in which the Crimson handily won 3-0.

Turning the tables the following day, McGill introduced Harvard to rugby, and the American team held their own, playing to a tie. The school fell in love with the game, a much more refined version than the states had seen in the 1850s.

In the fall, Harvard challenged Yale to the game, and though Yale lost, they too were engrossed in the sport. That love quickly spread across the Ivy League schools.

By 1879, Princeton, Harvard, Columbia, and Yale had joined to create the Intercollegiate Football Association.

It was a sport that Camp, who attended Yale, loved, too. And for good reason. He exceled at it with some calling him the best player in the sport. He was also regarded for being a highly intelligent person, a useful skill in a game that still came up with new problems to solve all the time. And the perfect man for creating a game.

Up to this point, we still have barely scratched the surface of American football. We’ve seen the game start with soccer and make the jump to rugby. But football this is still not.

Camp changed that.

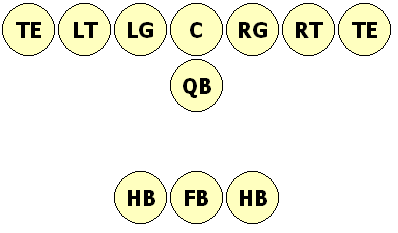

With a governing body established, all rule changes were held at conventions – think of it as today’s version of the owner’s meetings – in Massachusetts. The first breakthrough Camp made came in 1880. Rugby Code mandated 15 players to a side but Yale, who had been introduced to playing with 11 back in their soccer days, preferred the smaller number to open up the game.

After three years, he persuaded the IFA to make the switch. The first sign of a football landscape.

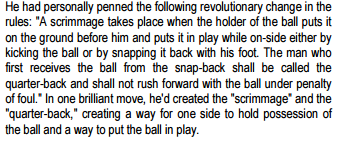

Though I can’t speak for the game today, rugby lacked much of a tactical element. By and large, it was just about the bigger, stronger group beating up on the other. Find ball, get ball. No possession, no ability to plan. In one move, Camp create a possession with a defined line of scrimmage for one team, a center to snap the ball, and a quarterback to receive it.

From the Pro Football Researcher’s article.

The size of the field was squeezed down to today’s standards – 110 by 53 1/3 yards. Football was starting to take shape but wasn’t quite there just yet.

There was a line of scrimmage, there was clear possession, but there was not a downs system. You may already see the problem.

A game in 1881 between Princeton and Yale became known as the infamous “block game.” With both teams undefeated but Yale the favorite, Princeton decided to hold the ball for the entire first half, avoiding giving Yale the ball and a chance for them to score. Yale responded in the same fashion in the second half and the game ended 0-0 in the most uneventful way possible.

The game frustrated fans and other players alike, so much so a faction formed who wanted to scrap the idea of a scrimmage and go back to old rugby rules. Football’s life hung in the balance.

It was Camp again to the rescue, instituting the first ever “downs” policy, stating that a team had three tries to make five yards.

With that rule implemented on October 12th, 1882, American football finally took shape. No question, still rough around the edges, the scoring system wasn’t modified to make touchdowns count the most for well over another year, but the look of the game finally fell in line.

Six years later, the finally remnants of the rugby game were eliminated. And four years after, the game became professional. In fact, it was in the Pittsburgh Steelers backyard when in 1892, William “Pudge” Heffelfinger – the person picture at the top of this article – was paid $500 in a contest between the Pittsburgh Athletic Club and Allegheny Athletic Association.

Though the sport wouldn’t find its footing for quite some time, the NFL wouldn’t even form for nearly another 30 years, and went through some dark times, the game’s origins have seemingly been overlooked. In a way, that’s understandable. The story doesn’t match the fast-paced action of today’s game.

But the history of the game has become an accepted myth and takes away from the fascination of its upbringing. The game didn’t just exist. It didn’t come together in an instant, from nothing to this exhilarating show of 4.3 40’s and pinpoint passes.

It was primitive, it was boring by today’s standards, but it was football.