Editor’s Note: This article was originally written on Feb. 10, 2020. We are running it again in celebration of Black History Month.

In 1933, linemen Ray Kemp became the first African American to ever wear a Pittsburgh Steelers (then the Pittsburgh Pirates) uniform, appearing in three games as a substitute tackle. At the time, he was one of just two Black players in professional football. There was also Joe Lillard, halfback for the Chicago Cardinals, playing from 1932 to 1933.

The league never officially segregated but it was an owner-wide understanding not to sign Black players. No other African American would play in the NFL until 1946, when running back Kenny Washington rebroke the color barrier for the Los Angeles Rams. Teams didn’t reintegrate all at once either. The final team to do it, Washington, waited until 1962 when it signed Bobby Mitchell and Ron Hatcher.

So what about Pittsburgh? When did the franchise reintegrate? History says very little.

Check the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s official list and it notes that FB Jack Spinks played for the Steelers in 1952. But he wasn’t the only one.

In fact, there were seven African-American players signed by Pittsburgh prior to the 1952 season. Spinks was one of only two to appear in a regular-season game, but all were trailblazers for their time, the first steps of eroding away football’s history of racism and bigotry.

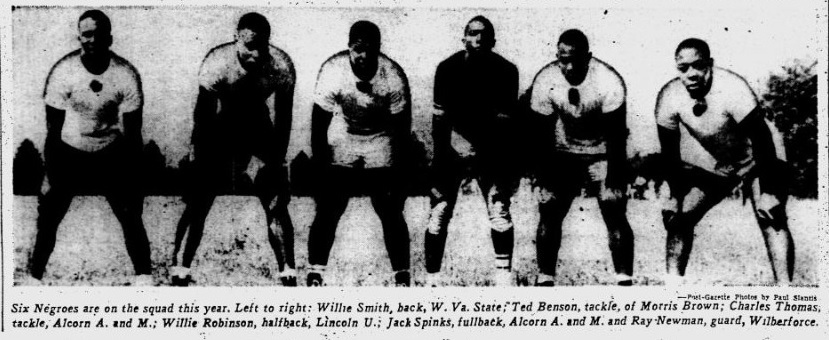

The seven Steelers are:

T Ted Benson

T Charlie Thomas

HB Bill Robinson

FB Jack Spinks

OG/T Ray Newman

HB “Suitcase” Willie Smith

HB Clyde Atkins

All of them deserve special recognition for their place in football history. That’s what we’ll do today.

Ted Benson – 6-5/245 T Morris Brown

Benson should be credited as the first Black player signed by the Pittsburgh Steelers. The now defunct Pittsburgh Press, the clipping shown below, noted he was signed March 2, 1952. He starred for four years at HBCU Morris Brown. Credit Kemp, the first Black Steeler, for pushing Benson through the door. He recommended Benson to new Steelers’ head coach Joe Bach.

There was a real opportunity for him to make the team as 1952 began with Ernie Stautner’s “don’t call it a holdout,” a term the team never officially used. Stautner owned a drive-in and a bus line back home in New York, needing to find someone to run those businesses before he could resume his football career. He didn’t report to camp until Aug. 5, missing roughly a week’s worth of practices. He wasn’t the only one. Star LB Jerry Shipkey spent time away from the team for an unspecified personal issue, returning Aug. 4, while end Hank Manarik missed the entire season with a detached retina suffered the year before. It would ultimately end his football career.

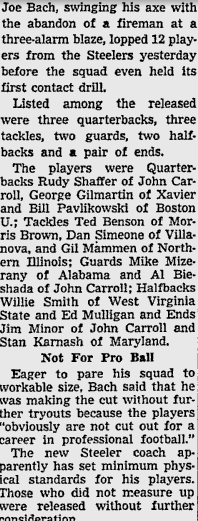

But Benson’s time in Pittsburgh was short-lived. Bach, installing the T formation (Pittsburgh was the NFL’s last to switch from the single wing), conducted physically demanding practices. After a “light” session on July 28, the team held its first real practice the 29th.

Benson, along with several others, were cut on the 30th, Bach declaring those players not physically fit enough to deserve a spot on the roster.

Switching sports, he briefly played basketball in the Eastern Basketball Association. In four games with the Hazelton Hawks, he averaged 12 points and 8.5 rebounds per game.

‘Suitcase’ Willie Smith – HB/West Virginia State

Some press clippings from the time only mention four Black players as being part of the ’52 camp roster: Benson, Thomas, Robinson, and Spinks. But earlier editions paint a different story. Like halfback “Suitcase” Willie Smith.

He grew up where pro football basically began. Born in Massillon, Ohio, in 1930, the Massillon Tigers were one of pro football’s early powerhouses, going undefeated in 1904, 1905, and 1907.

He attended West Virginia State – the same school as Bill Nunn, by the way – on athletic scholarship, playing basketball and football. His basketball team won the conference championship all four years he attended, and he was co-captain of the football team his senior year.

That’s also where he earned the nickname “Suitcase,” showing up at school with nothing but a lone suitcase.

Smith’s time in Pittsburgh was similar to Benson’s, one of 12 cut on July 30 for, in Bach’s mind, not being physically ready to compete.

“The new Steeler coach apparently has set minimum physical standards for his players. Those who did not measure up were released without further consideration.”

Although the timeline is unclear, he served as a second lieutenant in the Army during the Korean War before returning stateside and opening several businesses, including Beeson’s Video Parlor and Buddy’s Flame Restaurant and Lounge in the West Virginia and Washington, D.C., areas.

He was inducted into the West Virginia State Hall of Fame in 1986. Smith passed away Jan. 4, 2006, at the age of 75.

Ray Newman – OG/Central State (aka Wilberforce University)

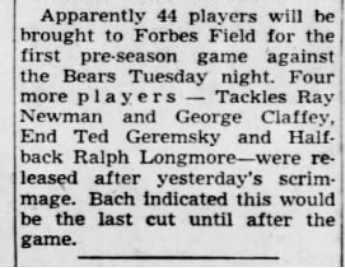

Newman, like Smith, was a name I came across along the way. Information on him is awfully scarce. He made it through the first week of Steelers practices but was released by Bach on Aug. 7, the final cutdown prior to the Steelers’ first preseason game.

The only two references I could find was the news he had been cut and a July 28 clipping indicating that he was part of the training camp roster. You also see his photo above. Wilberforce, where Newman attended, was the USA’s first private HBCU.

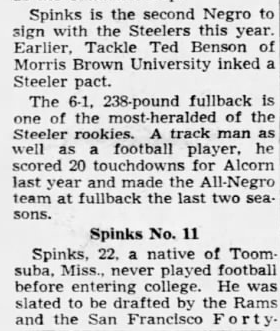

Jack Spinks/FB 6-0 238 Alcorn A&M

Spinks is the most well-known name on the list and the player the Hall officially recognizes as reintegrating the franchise. There’s some debate about which Black player was part of the Steelers first. As noted above, the Press says Benson was the first on the team in early March 1952. But Spinks and Bill Robinson were the first African-American players drafted in franchise history. The draft that year was held in January, two months before Benson’s deal. It seems Spinks signed his contract after Benson in the middle of March but who was “first” is more of a moot point here.

The 1952 draft was a historic one. Across the league, 10 black players were selected, starting with Ollie Matson, taken third overall by the Cardinals. Matson would be one of football’s greatest runners, ending his career only behind Jim Brown in all-purpose yards and inducted into Canton in 1972.

According to reports at the time, the Los Angeles Rams and San Francisco 49ers had interest in Spinks but thought they could sign him after the draft. Teams were surprised when Pittsburgh nabbed him in the 11th round.

Spinks played one season with Pittsburgh, that ’52 season, carrying the ball 22 times for 94 yards while chipping in two receptions. Here’s a clip of him, No. 37, taking this handoff before lateraling it to HB Fran Rogel.

He would play for three more teams during the rest of his NFL career: Chicago in 1953, Green Bay in 1955-1956, and the New York Giants in 1956-1957.

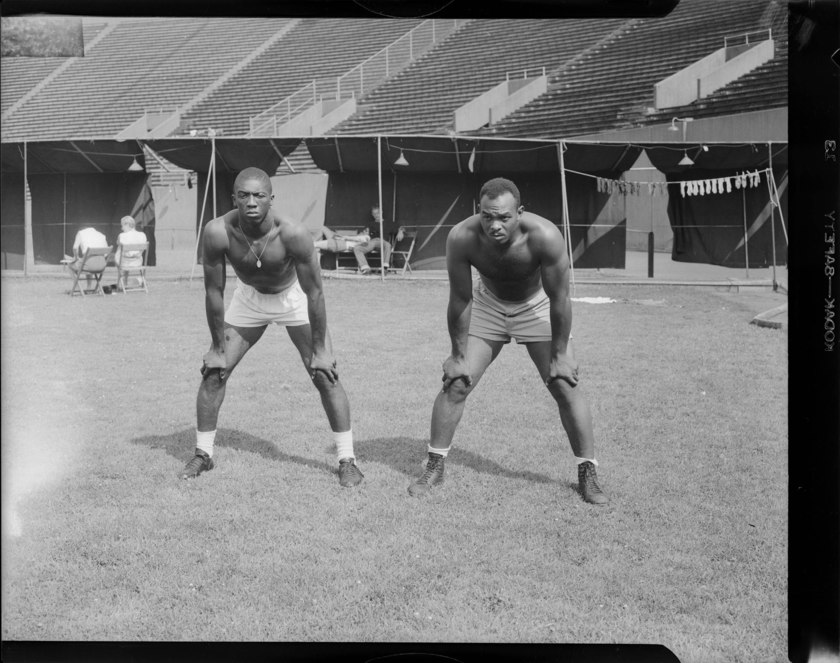

Here is an awesome, high-resolution photo of Spinks and Robinson, courtesy of the Carnegie Museum of Art. Robinson is on the left, Spinks on the right.

Bill Robinson – 6-0 205/HB Lincoln

Robinson was the second Black Steeler drafted, taken in the 25th round. A local product from Pittsburgh, Nunn, writing for the Pittsburgh Courier, predicted the team had interest in Robinson. No doubt the organization valued his columns and information, eventually leading to Nunn being convinced to join the front office. The Chief also reportedly knew Robinson growing up due to their local ties. Kemp, as we’ve noted, was the AD at Lincoln, where Robinson attended, and that may have had an influence in him getting drafted.

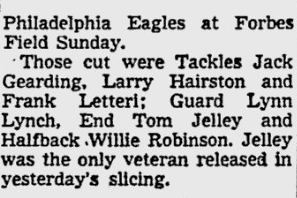

Pittsburgh released him on Sept. 23, five days before its first regular-season game against Philadelphia (the Steelers would lose, 31-25) as it whittled the roster down to 37, four above the league’s max. But he lasted through the preseason, meaning he logged actual snaps with the franchise.

He latched onto Green Bay later that year for at least a pair of games. After spending time in the CFL with Winnipeg — Robinson would later say he preferred playing up north due its collegiate feel — he circled back to the NFL eight years after entering it, spending one season with the New York Titans in their inaugural year in 1960.

Here’s a photo of Robinson and Spinks from Steelers training camp. The two showed up early to hit the ground running, despite Bach only mandating quarterbacks and centers to report about a week beforehand to prepare for running the T formation.

Charlie Thomas – 6-2 245/T Alcorn A&M

Thomas is the player whose Steelers’ tenure we know the least about. It’s difficult to find any sort of reference to him in any newspaper in any capacity: college, pros, anything about his life. We only have his photo in that group of six and a reference to him being on the roster. It’s unclear when the team released him.

At 6-2 ,245 pounds, he was one of the bigger players on the roster during his brief stay on the team.

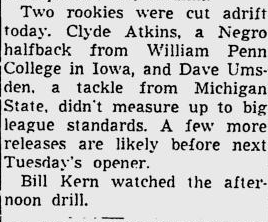

Clyde Atkins – HB/William Penn

Curiously, Atkins wasn’t even included in that group of six Black players shown above. But there is a reference to him when he was cut by the team on Aug. 6. It’s unknown when he was signed and possible he was brought onto the roster sometime right after training camp. That would explain why he wasn’t in the photo, which was taken in late July.

Before joining Pittsburgh, he spent part of the 1951 preseason with the Chicago Cardinals but broke two ribs in a game against the Green Bay Packers, squashing his chances of making the roster.

He was also an accomplished boxer and all-around athlete. Post-football, he married jazz singer Sarah Vaughan, though it lasted only from 1958-1963.